Foreword

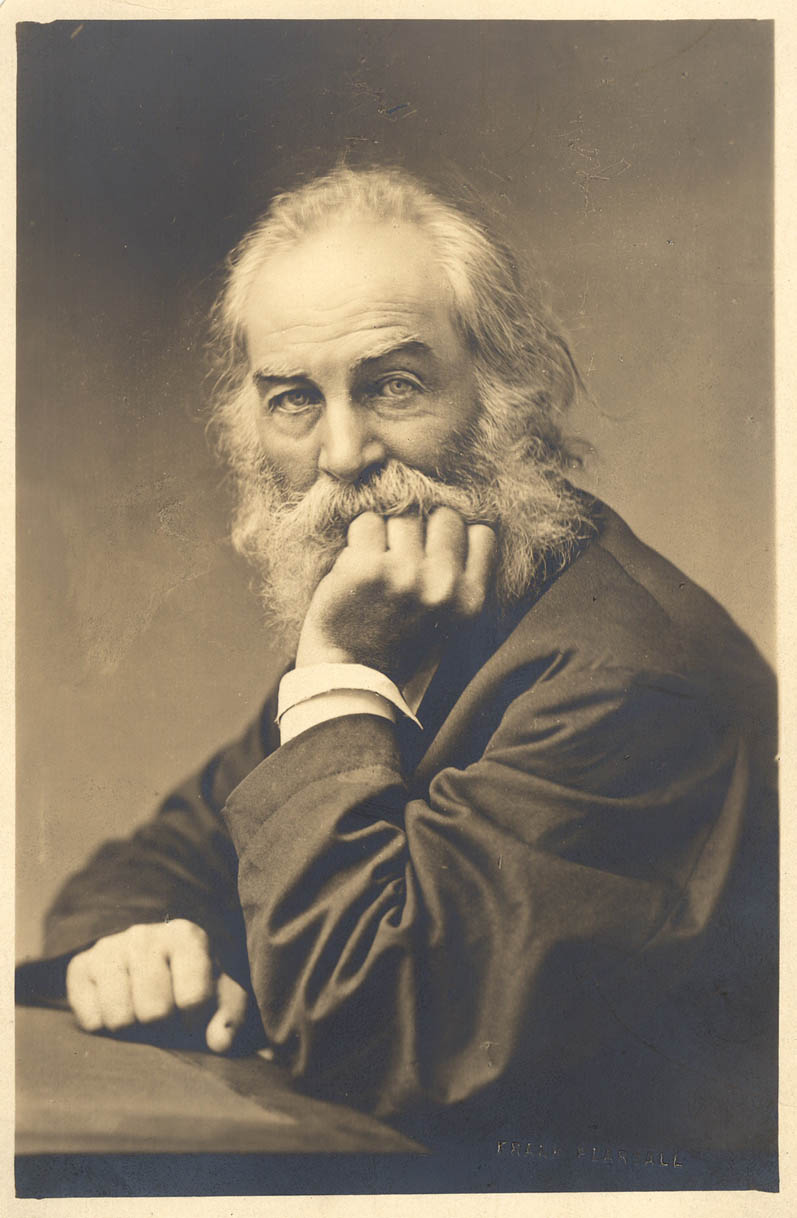

In most cultures, the meal table is a sacred space, an intimate place that gathers family and friends—those that we select out from the multitude. Whitman, in this section, sets a democratic table and cannot imagine why anyone would be excluded from taking part in “the meal equally set.” Whitman’s imagined meal is also, of course, this poem itself, another “table” offering a hearty fare, from which no reader is excluded. Poems, all books in fact, are open tables, unable finally to prevent anyone from partaking of them, even if most books are written with a particular audience in mind. But Whitman’s poem is special, because it is written precisely for an audience that potentially includes everyone, from the slave to the sinner to the thief to the prostitute.

The twentieth-century African American poet Langston Hughes wrote a poem responding to Whitman’s invitation to a democratic dinner. Entitled “I, Too,” Hughes’s poem begins by reminding Whitman that “I, too, sing America.” Whitman, as a white male, could easily claim that he was the poetic voice of the nation, but Hughes suggests that Whitman’s promised “meal equally set” has in fact still not been realized: “I am the darker brother. / They send me to eat in the kitchen / When company comes.” Still exiled from full participation in the democratic table, Hughes’s black narrator anticipates the day when finally “I'll be at the table / When company comes.” “I, too, am America,” he concludes. Such poems demonstrate how minority communities in America have taken heart from Whitman’s democratic invitation while simultaneously challenging his claims.

One remarkable aspect of this section is the way Whitman offers a haunting image of us reading the poem. Using the deictic word this and repeating it five times, Whitman draws our attention to this poem, this page, this moment when we are reading the poem. And he projects our physical presence, our “bashful hand” as it caresses the words on the page. His very words seem to look up from the page and see our hair, see our lips forming the words (like a kiss, lips upon lips), murmuring the poem’s message of unity, our face reflecting Whitman’s face through the face of the page. This poem, Whitman reminds us, is just another thing in nature, something we hold in our hands and gaze on in astonishment. At this moment, in this act of reading, “this hour,” it is only us and the poet, alone together: Whitman will tell us his deepest confidences, and at this moment, he tells them only to you. But, like the daylight, like a bird’s song, these words are indiscriminate—they do not discriminate—and are available to the eyes and ears of everyone.

- Foreword to Section 19

- Song of Myself, Section 19 —read by Eric Forsythe

- Afterword to Section 19

Afterword

Whitman’s “intricate purpose” in “Song of Myself,” spelled out in this section over a meal with the lowly and the scorned, is to upend our hierarchical view of the world: to his table everyone is invited, saint and sinner and all the rest. What astonishes (note that an obsolete meaning of the word is to “strike with sudden fear”), what the poet confides, is that “the thoughtful merge of myself, and the outlet again,” the issue of his acts of union and imagination, have revealed to him (when and where we do not know) that there is no hierarchy of values in nature or society, no difference between spring rain, the glint of mica in sunlight, and the song of the redstart, not to mention the concerns of any guest at the feast of life. No one can pull rank on another.

Whitman’s influence on subsequent generations of poets, prosodic and philosophical, can be measured in the proliferation of open forms marking contemporary American poetry and in a general democratic bearing toward the world, the recognition that literally anything can inspire new work. In “Spring Rain,” for example, Robert Hass imaginatively tracks a Pacific squall into several possible futures—as snow in the Sierras; as larkspur sprouting along a creek, propagated by the gray jays that eat the seeds; as the backdrop of drinking coffee with a friend, “the unstated theme” of the visit being “the blessedness of gathering and the blessing of dispersal.” This is the theme of every interaction, in human and nonhuman experience: we gather together, and then we go. It was Whitman who taught us how to make poetry out of that astonishing fact.

Question

What are the customs for setting a meal in your culture? Are there dining tables that are set on special occasions for more than family and friends? What occasions can you imagine that might necessitate a table to be set for “the wicked just the same as the righteous”?