Book review: 'English' + 'Foreign Words'

Two novels about falling in love with a language.

Wang Gang, English. 2004. Translated from the Chinese by Martin Merz and Jane Weizhen Pan. Viking, 2009.

Vassilis Alexakis, Foreign Words. Translated from the French by Alyson Waters. Autumn Hill Books, 2006.

At seven in the morning many years ago, my brother passed by my room and saw me with an Oxford Learner’s Dictionary in my lap. He shook his head in disbelief. We had just woken up and were going downstairs to eat the oatmeal our grandmother cooked for us before we left for school. In his mind it was too early for English; but I had heard a word I didn’t understand in a song on the radio. I remember it to this day: “manic” from the Bangles’ “Just Another Manic Monday.”

I am telling you this story to account for why I found so much in common with Love Liu, the teenage narrator of Wang Gang’s English, and with Nicolaides, the fifty-three-year-old Greek writer and fictional alter ego of Vassilis Alexakis in Foreign Words. The first is so obsessed with an English dictionary – reputedly the only one in the remote city of Urumqi – that he breaks a leg while trying to steal it from his English teacher’s room. The latter methodically reads the entire dictionary of Sango, an African language he decides to learn after his father’s death. A majority of language learning narratives I am familiar with are immigrant memoirs; they narrate stories of social and class mobility achieved thanks to the acquisition of a new language. In these two novels, a foreign language does not lead to a new life, but merely – if one can diminish its effects with a word choice like that – enriches life as it is.

Even though I read English mainly because it was a story of language learning, I ended up immersed in a cultural space – Urumqi, the capital of China's distant western province of Xinjiang – and moment – the Cultural Revolution – I knew little about. I learned to understand it intimately, on the level of feeling, early on in the novel. A particularly telling and memorable scene is when Love Liu’s father, painting a mural of Chairman Mao, gets reprimanded for representing the leader with only one ear. Although he tries to explain that when drawing a person looking to the side, the laws of perspective require the subject to be drawn with only one ear, he is asked (by having his own ear pulled) to add another ear. When this – unsurprisingly – does not look right to the supervisors, he is slapped while his twelve-year-old son looks on. The very act of painting from a different perspective is read as counterrevolutionary. The scene seems funny in some ways – imagine the Picasso effect of the ears added to Mao looking sideways – but this does not lessen the humiliation and unreasonable limitations the scene represents.

In an “Afterword,” the author tells us that he “chose not to overstate the cruelty of the era because it has already been recounted ad nauseam.” Understated, the cruelty touches the reader even more, because it allows us to chuckle at its slapstick nature before we realize the cruelty in ourselves that let us chuckle in the first place. Life in Urumqi abounds in violence: murders, suicides, and accidental deaths; repression, imprisonments, and daily uncertainty of who will be shunned and who executed; illicit relationships and strong hatreds. Adults slap each other to show and exert their power: their psyches clearly at their wit’s end, which trickles down to the children, like Love Liu’s teacher’s-pet friend, Sunrise Huang.

Even language instruction in Love Liu’s school is politically motivated and thus changeable. The Uygur teacher, the beautiful half-Uygur half-Han Ahjitai, leaves, just like the Russian teacher a year before her. When Russian is replaced with English, it is because the girls in the class have been hankering for it, we are told; but I am still wondering why they are allowed to learn the imperialist, enemy language in the first place? We know how difficult it is to obtain English language materials – hence Love Liu’s obsession with his teacher’s dictionary. But who decides the language is safe for the children to learn? The English teacher himself, a man from Shanghai called Second Prize Wang, with his all-too-Western gentlemanly manners, cologne and luxurious clothes, is perceived by the townspeople as a threat. While the locals see Second Prize Wang “poison” Love Liu with “his bourgeois influence,” Love Liu sees someone gentle and focused, someone who can help him grow up while his parents, architects employed in the Cultural Revolution’s war machine – his mother designing a bomb shelter, his father a hydrogen plant – remain too absent to take care of him.

The novel surprises us when Love Liu, after being such a diligent student of English, does not make it to the University and thus does not leave the provincial city he so longed to escape. Instead, he ends up replacing Second Prize Wang as the English teacher at his own school. Was it his politically suspicious behavior that disqualified him from the university, or was he really, as he suggests in the novel, unable to pass the exam? If so, it is a surprising ending to a Künstlerroman, because although the novel promises Love Liu will transcend the margins of his Urumqi life, he does so only virtually, through the study of English.

A few words on the translation, since the translators made some meaningful decisions about the title and characters’ names. The decision to render the leading characters’ names in English lends the book an aura of an allegory, in the vein of Everyman or The Pilgrim’s Progress. But while their terse nicknames mean so much beyond who they are, the characters are far from allegorical: fully rounded, vulnerable, and believable. The title and its translation provide another interesting story; the Chinese title is a phonetic rendering of the word 'English' transliterated as if by a beginning learner. In the novel students first learn to speak English in this way, before they proceed to what is called “Linguaphone” English. The English translation misses this subtlety. On the difficulties of "foreignizing foreignness" in translation see the interview with Martin Merz and Jane Weizhen Pan, co-translators of the novel.

Vassilis Alexakis’ Foreign Words is an exercise in allowing the foreign sound foreign, and letting the novel read like a language textbook at times. By the end of the novel – which begins with what becomes a refrain, “Baba ti mbi a kui” or “my father is dead” – a careful reader should be able to comprehend a whole paragraph of Sango. Since his mother died not long before, Nicolaides has to learn how to deal with being an orphan, and novels, for him, always deal with discovery, or loss, or both. Here, the discovery pertains to the world of a new language and loss is his parents’ deaths. Unable to write “my father is dead” neither in his native Greek nor in his adopted French, the narrator balances the process of mourning with the excitement of language learning.

The novel on the whole is a meditation on language, migration, and return. An immigrant in France, the narrator knows French so intimately that it no longer feels like a foreign language; so when he decides to learn another language, he looks for something genuinely different, because Italian, for example, is for him, “like French dressed up in party clothes.” Still, he cherishes the multiple volumes of Le Grand Robert, an authoritative dictionary of French he receives from his editor. He even buys a new bookcase to house the gift. The one volume of the Sango dictionary, thin in comparison, the narrator reads through in its entirety. He chooses Sango over any other African language because of the border-crossing histories of his own family, encapsulated in an old photograph of his grandfather taken at the Studio de Paris in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic. He imagines a connection to the Greek diaspora in Bangui, but when he visits, he realizes that very few people are left, and they no longer feel they belong in Greece.

Nicolaides does not shy away from the political dimensions of language learning and instruction. He comments on the reasons for languages to penetrate into each other and claims that soon “current events” will force us to understand African words, just as it has been the case with the Arabic ones, for example jihad and ayatollah. When he travels to the Central African Republic, a lecture he gives describing his own process of learning Sango stimulates a post-colonial controversy over the necessity of the language being taught in schools. After his lecture, the French ambassador’s wife asks whether Sango is a real language and so emphasizes the legacies of colonization.

But Foreign Words is not merely a narrativized treatise on language and migration; it abounds in lyrical insights, couched in beautiful language. It reminded me of Julio Cortázar’s Rayuela with its haphazard Paris life of immigrant writers surviving on the advances from their editors. Here, however, the set of characters is much smaller: a friend diagnosed with leukemia and his much younger lover, Nicolaides’ own lover, a married midwife, and the writer’s editor. And none of the living characters are as important as the deceased parents, or indeed as Sango, the personified language: “Languages return the interest you show in them. They tell you stories only to encourage you to tell your own.... Foreign words are compassionate. They are moved by the least little sentence you write in their language, and it doesn't matter if it's filled with mistakes.”

Ania Spyra is professor of English and Comparative Literature at Butler University. She has published articles on multilingualism and transnationalism, feminist contestations of cosmopolitanism, and on nodal cities, most recently in American Book Review and Contemporary Literature.

8.1 Spring 2015

Editorial

The postcard

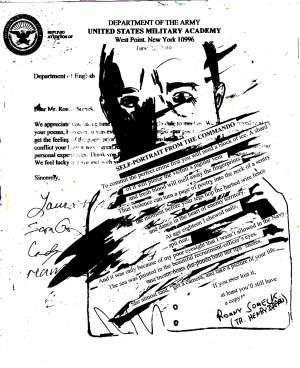

- Ronny SOMECK / Self-Portrait of the Commando

Fiction

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Blindfolded and bound in the boot of an unmarked police car, the boy was delivered to the House of Stories...

- Marie-Louise Bibish MUMBU / Me and My Hair

The Bana mboka, the kids from here, versus the Diaspora, those who banished themselves. Fresh-Bagged versus The Bottled Stuff. Rainy Season versus Winter. Stayed versus Left. On Foot versus Driving. Boubou against Low-Waisted Pants...

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Poetry

- Ariane Dreyfus translated from the French by Corinne Noirot + Elias Simpson

- R. M. Rilke in new translations by Mark S. Burrows

- Shah Hussein and Naveed Alam in a Punjabi-English dialogue. With a preface, and an interview conducted by Spring Ulmer

Non-Fiction

- Michael Zeller / India. Walking. Translated from the German by Joseph Swann

- Sadek Mohammed (Iraq), Boaz Gaon (Israel), Mujib Mehrdad (Afghanistan) on writing in a country at war

Book review