Whitman wrote about the Civil War in many forms, contexts, and situations. He kept notes in multiple small notebooks he carried with him while he visited wounded and sick soldiers in the teeming hospitals of the nation’s capital. Often, while sitting by the bed of a suffering soldier, he would jot down what the soldier told him. Out of these notebooks—which record his visits to thousands of soldiers, listing their names, their home states, their wounds or illnesses, and often noting the stories of their lives on the march or in battle—he crafted many of his Civil War poems. He also mined these notebooks for the dispatches he wrote for multiple newspapers (including the New York Times) about the war and about his work in the hospital. Then he used those journalistic pieces to create his Memoranda During the War and Specimen Days. He also returned to those notebooks when he wrote his letters, which contain some of his most powerful Civil War writing. For Whitman, the borders between informal notebook writing, journalism, poetry, and correspondence were porous, and we can often find the same images appearing in prose and poetry, in scrawled notes and in published poems. Whitman’s tendency to meld and merge poetry and prose is evident from the 1850s on, but it increases during the years he experienced the war in Washington, D.C. Passages from his poetry frequently sound like they could be from his letters or his newspaper writing, and passages in his letters can often be lined to form poetry.

Whitman’s remarkable letter to Margaret Curtis is in response to a letter she wrote to him on October 1. She sent the poet $30 and explained how she and her husband, a Boston counselor, had listened to someone reading aloud a letter that Whitman had written to Dr. LeBaron Russell, a Boston physician who also had sent Whitman money to support his hospital work: “It was with exceeding interest that Mr Curtis & I listened to the letter you lately wrote to Dr. Russell, which came to us through my sister Miss Stevenson. Its effect was to make us desire to aid you in the good work you are engaged in,—caring for the sick & wounded soldiers. We inclose thirty dollars, & feel very glad to have the opportunity to minister to their comfort.” What we see here, as the critic Martin Buinicki has recently demonstrated, is an early fundraising network. Whitman’s letters to donors present the often heartbreaking details of soldiers’ suffering and underscore the efficacy of the small gifts that Whitman was able to distribute in the hospitals as a result of the money he received. Whitman presents the horrific details of the hospitals so that people like Dr. Russell and Margaret Curtis will read these letters to their friends, pass them around so that others may read them, and thus encourage an ever-broadening group to support the poet’s work. Whitman’s youngest brother Jeff, who never served in the war, often coordinated his brother’s fundraising work, reminding Walt to write letters—the more detailed the better—to every donor. As Buinicki shows, Whitman and his brother developed an informal fundraising network that anticipated the more sophisticated mechanized networks that charities use to raise money today. The raw emotion of Whitman’s letters, expressed with aching sincerity, brought in just enough money to allow Whitman to carry on a quite miraculous series of hundreds of exhausting hospital visits, ultimately taking him to the bedsides of as many as 100,000 soldiers, distributing modest treats and providing something far more important—deep affection for stranger after stranger.

Whitman was given an appointment by the U.S. Christian Commission, an organization run by Protestant ministers and established to aid soldiers in hospitals (unlike the more formally constituted U.S. Sanitary Commission, which devoted itself more to mending soldiers in order to return them to the battlefields). Whitman’s notoriety as an “immoral” poet and his lack of church membership made his affiliation with the Christian Commission a tenuous one, however, and he ended up operating very much on his own, distributing an unsanctioned array of gifts, from brandy to small amounts of money to candy, ice cream, and fruit: religious comfort was not what Whitman offered, opting instead for the physical, bodily comforts of touch. He sat and held severely wounded soldiers—what he called “the cases that need special attention”—and kissed them, and he developed a complex and multifaceted relationship with many of them—partly paternal, partly fraternal; partly erotic; and, importantly, partly maternal, as he nurtured the wounded, prepared their food, and fed them: “one must be calm & cheerful, & not let on how their case really is, must stop much with them, find out their idiosyncrasies—do any thing for them—nourish them, judiciously give the right things to drink—bring in the affections, soothe them, brace them up, kiss them, discard all ceremony, & fight for them, as it were, with all weapons.” In Whitman’s mind, he was fighting a war every night in the army hospitals, but his weapons were the healing arts of affection and love, the delight of small gifts and casual kisses. And the object in Whitman’s war was life, not death, though death often came. Whitman could sense that his work—taking him to the hospitals where the fewest people visited—was ultimately the work of a “womanly soul” that gave him perhaps the most surprising gift of all, the gift of happiness in a place of “amputations, blood, death”: “I need not tell your womanly soul,” he writes to Margaret Curtis, “that such work blesses him that works as much as the object of it. I have never been happier than in some of these hospital ministering hours.”

—EF

Washington, | Armory Sq Hospital,

Sunday evening Oct 4

Dear Madam,

Your letter reached me this forenoon with the $30 for my dear boys, for very dear they have become to me, wounded & sick here in the government hospitals—As it happens I find myself rapidly making acknowledgment of your welcome letter & contribution from the midst of those it was sent to aid—& best by a sample of actual hospital life on the spot, & of my own goings around the last two or three hours—As I write I sit in a large pretty well-fill'd ward by the cot of a lad of 18 belonging to Company M, 2d N Y cavalry, wounded three weeks ago to-day at Culpepper—hit by fragment of a shell in the leg below the knee—a large part of the calf of the leg is torn away, (it killed his horse)—still no bones broken, but a pretty large ugly wound—I have been writing to his mother at Comac, Suffolk co. N Y—She must have a letter just as if from him, about every three days—it pleases the boy very much—has four sisters—them also I have to write to occasionally—Although so young he has been in many fights & tells me shrewdly about them, but only when I ask him—He is a cheerful good-natured child—has to lie in bed constantly, his leg in a box—I bring him things—he says little or nothing in the way of thanks—is a country boy—always smiles & brightens much when I appear—looks straight in my face & never at what I may have in my hand for him—I mention him for a specimen as he is within reach of my hand & I can see that his eyes have been steadily fixed on me from his cot ever since I began to write this letter.

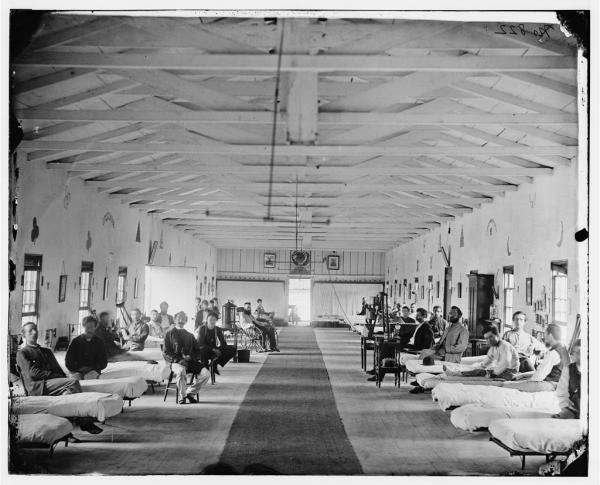

There are some 25 or 30 wards, barracks, tents, &c in this hospital—This is ward C, has beds for 60 patients, they are mostly full—most of the other principal wards about the same—so you see a U S general hospital here is quite an establishment—this has a regular police, armed sentries at the gates & in the passages &c.—& a great staff of surgeons, cadets, women & men nurses &c &c. I come here pretty regularly because this hospital receives I think the worst cases & is one of the least visited—there is not much hospital visiting here now—it has become an old story—the principal here, Dr Bliss, is a very fine operating surgeon—sometimes he performs several amputations or other operations of importance in a day—amputations, blood, death are nothing here—you will see a group absorbed [in] playing cards up at the other end of the room.

I visit the sick every day or evening—sometimes I stay far in the night, on special occasions. I believe I have not missed more than two days in past six months. It is quite an art to visit the hospitals to advantage. The amount of sickness, and the number of poor, wounded, dying young men are appalling. One often feels lost, despondent, his labors not even a drop in the bucket—the wretched little he can do in proportion. I believe I mentioned in my letter to Dr Russell that I try to distribute something, even if but the merest trifle, all round, without missing any, when I visit a ward, going round rather rapidly—& then devoting myself, more at leisure, to the cases that need special attention. One who is experienced may find in almost any ward at any time one or two patients or more, who are at that time trembling in the balance, the crisis of the wound, recovery uncertain, yet death also uncertain. I will confess to you, madam, that I think I have an instinct & faculty for these cases. Poor young men, how many have I seen, & known—how pitiful it is to see them—one must be calm & cheerful, & not let on how their case really is, must stop much with them, find out their idiosyncrasies—do any thing for them—nourish them, judiciously give the right things to drink—bring in the affections, soothe them, brace them up, kiss them, discard all ceremony, & fight for them, as it were, with all weapons. I need not tell your womanly soul that such work blesses him that works as much as the object of it. I have never been happier than in some of these hospital ministering hours.

It is now between 8 & 9, evening—the atmosphere is rather solemn here to-night—there are some very sick men here—the scene is a curious one—the ward is perhaps 120 or 30 feet long—the cots each have their white musquito curtains—all is quite still—an occasional sigh or groan—up in the middle of the ward the lady nurse sits at a little table with a shaded lamp, reading—the walls, roof, &c are all whitewashed—the light up & down the ward from a few gas-burners about half turned down—It is Sunday evening—to-day I have been in the hospital, one part or another, since 3 o'clock—to a few of the men, pretty sick, or just convalescing & with delicate stomachs or perhaps badly wounded arms, I have fed their suppers—partly peaches pealed, & cut up, with powdered sugar, very cool & refreshing—they like to have me sit by them & peal them, cut them in a glass, & sprinkle on the sugar—(all these little items may-be may interest you).

I have given three of the men, this afternoon, small sums of money—I provide myself with a lot of bright new 10ct & 5ct bills, & when I give little sums of change I give the bright new bills. Every little thing even must be taken advantage of—to give bright fresh 10ct bills, instead of any other, helps break the dullness of hospital life—

To read a poet’s correspondence is to be reminded of the gulf that lies between life and art. For if poetry is language in its most condensed form, a distillation of words and phrases and sentences into a musical arrangement capable of quickening the heart and mind, then letters composed or dashed off (as the case may be) by a poet whose eyes are not fixed on eternity may reveal the secret sources of his or her enduring literary works. This is certainly true of Whitman’s correspondence, which like that of most poets is a mixture of business, gossip, ideas, information, and reflections. He submitted poems to editors, often with an imperious air; solicited help in securing employment (his letter of recommendation from Ralph Waldo Emerson to Secretary of State William H. Seward is a model of tact); and detailed what he saw and heard. His letter thanking Margaret S. Curtis for her gift of $30 to be distributed among the wounded soldiers is no ordinary thank-you note; for he describes at some length what life is like on the wards, offering his benefactress an accounting of the uses to which he puts her largesse and a vision of the tragic reality wrought by war. His courtesy serves as both a lubricant for his supplication and an excuse to pay closer attention to men whose lives hang in the balance, leavened by the gifts he bestows on them.

“It is quite an art to visit the hospitals to advantage,” Whitman writes, by which he means finding ways to make himself useful in the midst of so much suffering. His ability to identify those who would appreciate what he had to offer was inseparable from his poetic instinct—the skill set born of talent, sympathy, and experience, which he brought to the page; another advantage of his caring for the wounded thus accrued to the literature of war. “Every little thing even must be taken advantage of—to give bright fresh 10ct bills, instead of any others, helps break the dullness of hospital life.” Poetry can do that, too, burnishing small details until they shine.

“I have been thinking of Whitman’s huge sweep,” Robert Lowell wrote to Elizabeth Bishop in the summer of 1966, “mostly in his thirties and forties, lines pouring out, a hundred poems a year, yet with long, idle afternoons of sauntering, chatting, at ease nearly with what the eye fell on.” With his fiftieth birthday approaching, Lowell dreamed of taking a long break, his life having grown altogether too complicated. But Whitman must have felt the same during the war, his days of ease giving way to the frenetic routine that ultimately ruined his health. Both men, broken by the years, nevertheless managed to turn their pain into art.

Whitman’s attention to the soldiers was not uniformly welcomed by hospital staff. “There comes that odious Walt Whitman to talk evil and unbelief to my boys,” one nurse wrote to her husband. That feeling persists in some quarters, prompting the poet Norman Dubie to write: “I worked on the wards for years, and have no patience with individuals who despise, as erotic, Whitman’s nursing practices in the field hospitals of Washington. The very best nursing I witnessed was done by women with a major obsession and grace that were both founded by Eros.” To Margaret Curtis Whitman confided that “such work blesses him that works as much as the object of it. I have never been happier than in some of these hospital ministering hours.” There are worse ways to spend an evening than comforting someone in pain.

—CM

Compare Whitman’s letter to donor Margaret Curtis with recent appeals for funds that you have received from charity organizations or with charity advertisements that you have seen on television. What are the similarities and the differences?

Answer this question in the Comment box below or on WhitmanWeb’s Facebook page.