When Whitman revised Memoranda During the War to include it in his longer autobiographical work called Specimen Days, one of the most significant changes he made was to turn a major part of the Memoranda introduction into the Specimen Days conclusion. Whitman knew what T.S. Eliot was to express many years later in his poem “Little Gidding”: “What we call the beginning is often the end /And to make an end is to make a beginning. / The end is where we start from.” Whitman certainly started his book about the Civil War at the end of the war, which, for him, was the beginning of writing a book about the war. But he knew as he began that there would be no ending, because, as he famously said in the conclusion of the Civil War section of Specimen Days, “the real war will never get in the books.” Whitman already knew that this war would be endlessly written about (he probably would not be surprised to find that the Library of Congress estimates around 75,000 books about the Civil War have now appeared, and more are always on the way), and he was certain that none of those books (including his own) would capture “the real war.” The war—its causes, its battles, its strategies, its horrors, its statistics—would be played and replayed, revised and rethought, argued over and forever debated, written and rewritten. Each new book about the war begins again to narrate it to its end, only for others to begin again. (And, as we look around this still-divided nation, we may ask if in fact the Civil War has ever ended, or whether it has simply begun again and again in various guises.)

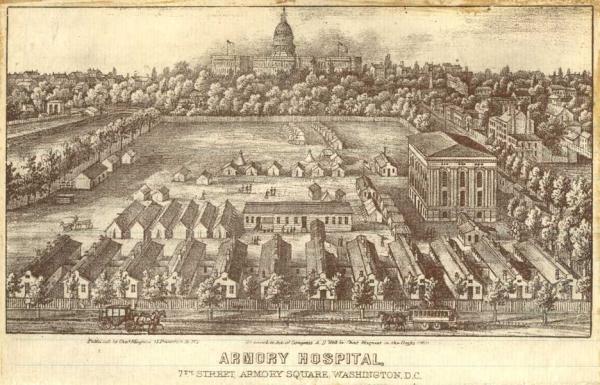

Whitman can only hint at what he means by the “real war”: he talks about its “interior history,” the way it was experienced by “the actual Soldier of 1862–’65, North and South, with all his ways, his incredible dauntlessness, habits, practices, tastes, language, his appetite, rankness, his superb strength and animality, lawless gait, and a hundred unnamed lights and shades of camp.” And what he hopes his book can do is “furnish a few stray glimpses into that life, and into those lurid interiors of the period,” even while he knows these lost experiences can “never . . . be fully convey'd to the future.” The war experience he knows best—those hundreds of thousands of sick, wounded, and dying soldiers in the hospitals of the nation’s capital—is the one, he believes, that will be least captured by books: “the marrow of the tragedy [is] concentrated in those Hospitals—(it seem'd sometimes as if the whole interest of the land, North and South, was one vast central Hospital, and all the rest of the affair but flanges).” The best we can hope will “ever [be] told or written,” Whitman tells us, are a “few scraps and distortions.” “Think how much,” Whitman writes, “and of importance, will be—how much, civic and military, has already been—buried in the grave, in eternal darkness.” Like those hundreds of thousands of graves of soldiers—all of whom are now “unknown” because they died too young ever to form the kinds of full identities that we could begin to know—the intense and lived experiences of the war are also now in their own unmarked graves, never to be brought to light.

In an earlier section of Memoranda, Whitman thought about the wounds and diseases he had seen in the hospitals during and right after the war: “A large majority of the wounds are in the arms and legs. But there is every kind of wound, in every part of the body. I should say of the sick, from my observation, that the prevailing maladies are typhoid fever and the camp fevers generally, diarrhœa, catarrhal affections and bronchitis, rheumatism and pneumonia. These forms of sickness lead; all the rest follow. There are twice as many sick as there are wounded.” This, for Whitman, was the key: the war was experienced in the body, on the body, and by the body. Whitman himself felt it in every fiber of his physical being; we have seen, over the past weeks, just how intensely the experience affected him, what a physical toll it took. In 1891, Whitman would add a final “concluding note” to Leaves of Grass, in which he traces his “late-years palsied old shorn and shell-fish condition” to his Civil War experiences: “the indubitable outcome and growth . . . of too over-zealous, over-continued bodily and emotional excitement and action through the times of 1862, ’3, ’4, and ’5, visiting and waiting on wounded and sick army volunteers, both sides.” That “bodily and emotional excitement and action” and strain is what will “never get into the books,” because what is missing from any writing is the body itself that experienced what the words can only point to, mutely. “Will the America of the future—will this vast rich Union ever realize what itself cost, back there after all?”

This, of course, is why Whitman wrote about the war, to offer a few scraps that might indicate the physical and emotional cost of those years of fratricide. Even if his own books failed to capture the “real war,” he nonetheless created a new way to represent war, one that has had a major impact on Civil War history in recent decades—as he turned his descriptions from a focus on the battlefields to a focus on the end results of those battles, the casualties in the hospitals; as he turned from the generals who designed war strategies to the troops who put their bodies onto and often into the fields. Just as in his prewar poetry Whitman broke down hierarchies and helped us see things democratically, so in his war writing did he break down the traditional ways of narrating war by making us painfully aware of the trials and heroism and horror and courage of the ordinary soldiers from all over the divided nation, whom he tended and loved and remembered. Those often forgotten soldiers who were taken off the battlefield by illness, injury, and death are illuminated in Whitman’s books as the war itself is re-centered on the hospitals. The people who so often don’t get in the books—and the messiness and carnage that they bring with them—do get in Whitman’s and form the very heart of his Civil War writing.

—EF

DURING the Union War I commenced at the close of 1862, and continued steadily through '63, '64 and '65, to visit the sick and wounded of the Army, both on the field and in the Hospitals in and around Washington city. From the first I kept little note-books for impromptu jottings in pencil to refresh my memory of names and circumstances, and what was specially wanted, &c. In these I brief'd cases, persons, sights, occurrences in camp, by the bedside, and not seldom by the corpses of the dead. Of the present Volume most of its pages are verbatim renderings from such pencillings on the spot. Some were scratch'd down from narratives I heard and itemized while watching, or waiting, or tending somebody amid those scenes. I have perhaps forty such little note-books left, forming a special history of those years, for myself alone, full of associations never to be possibly said or sung. I wish I could convey to the reader the associations that attach to these soil'd and creas'd little livraisons, each composed of a sheet or two of paper, folded small to carry in the pocket, and fasten'd with a pin. I leave them just as I threw them by during the War, blotch'd here and there with more than one blood-stain, hurriedly written, sometimes at the clinique, not seldom amid the excitement of uncertainty, or defeat, or of action, or getting ready for it, or a march. Even these days, at the lapse of many years, I can never turn their tiny leaves, or even take one in my hand, without the actual army sights and hot emotions of the time rushing like a river in full tide through me. Each line, each scrawl, each memorandum, has its history. Some pang of anguish—some tragedy, profounder than ever poet wrote. Out of them arise active and breathing forms. They summon up, even in this silent and vacant room as I write, not only the sinewy regiments and brigades, marching or in camp, but the countless phantoms of those who fell and were hastily buried by wholesale in the battle-pits, or whose dust and bones have been since removed to the National Cemeteries of the land, especially through Virginia and Tennessee. (Not Northern soldiers only—many indeed the Carolinian, Georgian, Alabamian, Louisianian, Virginian—many a Southern face and form, pale, emaciated, with that strange tie of confidence and love between us, welded by sickness, pain of wounds, and little daily, nightly offices of nursing and friendly words and visits, comes up amid the rest, and does not mar, but rounds and gives a finish to the meditation.) Vivid as life, they recall and identify the long Hospital Wards, with their myriad-varied scenes of day or night—the graphic incidents of field or camp—the night before the battle, with many solemn yet cool preparations—the changeful exaltations and depressions of those four years, North and South—the convulsive memories, (let but a word, a broken sentence, serve to recall them)—the clues already quite vanish'd, like some old dream, and yet the list significant enough to soldiers—the scrawl'd, worn slips of paper that came up by bushels from the Southern prisons, Salisbury or Andersonville, by the hands of exchanged prisoners—the clank of crutches on the pavements or floors of Washington, or up and down the stairs of the Paymasters' offices—the Grand Review of homebound veterans at the close of the War, cheerily marching day after day by the President's house, one brigade succeeding another until it seem'd as if they would never end—the strange squads of Southern deserters, (escapees, I call'd them;)—that little genre group, unreck'd amid the mighty whirl, I remember passing in a hospital corner, of a dying Irish boy, a Catholic priest, and an improvised altar—Four years compressing centuries of native passion, first-class pictures, tempests of life and death—an inexhaustible mine for the Histories, Drama, Romance and even Philosophy of centuries to come—indeed the Verteber of Poetry and Art, (of personal character too,) for all future America, (far more grand, in my opinion, to the hands capable of it, than Homer's siege of Troy, or the French wars to Shakspere ;)—and looking over all, in my remembrance, the tall form of President Lincoln, with his face of deep-cut lines, with the large, kind, canny eyes, the complexion of dark brown, and the tinge of wierd melancholy saturating all.

More and more, in my recollections of that period, and through its varied, multitudinous oceans and murky whirls, appear the central resolution and sternness of the bulk of the average American People, animated in Soul by a definite purpose, though sweeping and fluid as some great storm—the Common People, emblemised in thousands of specimens of first-class Heroism, steadily accumulating, (no regiment, no company, hardly a file of men, North or South, the last three years, without such first-class specimens.)

I know not how it may have been, or may be, to others—to me the main interest of the War, I found, (and still, on recollection, find,) in those specimens, and in the ambulance, the Hospital, and even the dead on the field. To me, the points illustrating the latent Personal Character and eligibilities of These States, in the two or three millions of American young and middle-aged men, North and South, embodied in the armies—and especially the one-third or one-fourth of their number, stricken by wounds or disease at some time in the course of the contest—were of more significance even than the Political interests involved. (As so much of a Race depends on what it thinks of death, and how it stands personal anguish and sickness. As, in the glints of emotions under emergencies, and the indirect traits and asides in Plutarch, &c., we get far profounder clues to the antique world than all its more formal history.)

Future years will never know the seething hell and the black infernal background of countless minor scenes and interiors, (not the few great battles) of the Secession War; and it is best they should not. In the mushy influences of current times the fervid atmosphere and typical events of those years are in danger of being totally forgotten. I have at night watch'd by the side of a sick man in the hospital, one who could not live many hours. I have seen his eyes flash and burn as he recurr'd to the cruelties on his surrender'd brother, and mutilations of the corpse afterward. [See, in the following pages, the incident at Upperville—the seventeen, kill'd as in the description, were left there on the ground. After they dropt dead, no one touch'd them—all were made sure of, however. The carcasses were left for the citizens to bury or not, as they chose.]

Such was the War. It was not a quadrille in a ball-room. Its interior history will not only never be written, its practicality, minutia of deeds and passions, will never be even suggested. The actual Soldier of 1862–'65, North and South, with all his ways, his incredible dauntlessness, habits, practices, tastes, language, his appetite, rankness, his superb strength and animality, lawless gait, and a hundred unnamed lights and shades of camp—I say, will never be written—perhaps must not and should not be.

The present Memoranda may furnish a few stray glimpses into that life, and into those lurid interiors of the period, never to be fully convey'd to the future. For that purpose, and for what goes along with it, the Hospital part of the drama from '61 to '65, deserves indeed to be recorded—(I but suggest it.) Of that many-threaded drama, with its sudden and strange surprises, its confounding of prophecies, its moments of despair, the dread of foreign interference, the interminable campaigns, the bloody battles, the mighty and cumbrous and green armies, the drafts and bounties—the immense money expenditure, like a heavy pouring constant rain—with, over the whole land, the last three years of the struggle, an unending, universal mourning-wail of women, parents, orphans—the marrow of the tragedy concentrated in those Hospitals—(it seem'd sometimes as if the whole interest of the land, North and South, was one vast central Hospital, and all the rest of the affair but flanges)—those forming the Untold and Unwritten History of the War—in-finitely greater (like Life's) than the few scraps and distortions that are ever told or written. Think how much, and of importance, will be—how much, civic and military, has already been—buried in the grave, in eternal darkness !....... But to my Memoranda.

If it is true that “the real war will never get in the books,” as Whitman observes in Specimen Days, then the question arises: what does appear in the poetry, fiction, essays, reminiscences, histories, journals, and other works about the war, in his time and down through the generations? The Library of Congress calculates that approximately 75,000 books have been published on the Civil War—more than one a day since Appomattox—and if you add films, television shows, and video games, not to mention songs, symphonies, and operas, it becomes clear that there has been, and likely will continue to be, no shortage of works about this defining event of American history, each of which portrayed something about the war, essential or peripheral, true or false. But the real war—where is it to be found, if not in books, and films, and music?

Some years ago, at a meeting in Nairobi of writers and scholars who were designing a new university for the Agha Khan, a novelist suggested that in addition to gathering books, periodicals, papers, films, sound recordings, and digital archives, the library would collect and catalogue smells from around the world, natural and manmade—rose blossoms, car exhaust, pine pitch, smoke and sweat, nectar and silver polish, the tang of the sea, the taste of sautéed onions, the stench of death: a gallery of fragrances, ordered from the rank to the sublime, available to perfumers, pathologists, and anyone seeking to identify a particular aroma. The idea never progressed beyond the drawing board, confirming the wisdom of Robert Hass’s insight: “There are limits to imagination.” But perhaps the novelist will work this idea into a book, inspiring an enterprising librarian to create an olfactory gallery. In the meantime it may help to explain why the volume of corpses decomposing in the earth convinced Whitman that the real war would lie forever beyond any medium of artistic expression. How to translate the mingled odors of grass and gangrene?

Geoffrey Hill’s meditations on the problem of evil include these memorable lines: “Art is impregnable in its claims,/ Consoles itself while children curl in flames./ I could not say what registers the shock.” Whitman was shocked by the amount of blood spilled in the Civil War; the scale of loss, personal and collective, broke his health and spirits. But what he registered in his writings ensures that the carnage at the heart of American history can still shape the sensibilities of a people who daily register new shocks in their ongoing experiment in liberty.

—CM

William Faulkner wrote that “The past is never dead. In fact it’s not even past.” This is another way of construing Eliot’s idea that “the end is where we start from” and Whitman’s claim that “the real war will never get in the books.” All three of these statements express the realization that we can never access the body of the past, the physical experience that people now dead once felt in the very fiber of their bodies. But we can also nevernot want to access that past, to think, imagine, and write our way back to an imagination of what those bodies must have felt. Often our own past feels this way, too—we recall feeling pain or horror or terror, but it is difficult to “get it in the books,” to write it so that others can experience in their bodies what we felt in ours (or so that we can once again feel what we know we once felt). Writers often experience most keenly this notion that “the past is never dead” and that we are always starting at the end. Try writing about a past event that has caused you to feel intensely and deeply and physically, and describe it in such a way that you emphasize what the body felt. How close can you get to having your words bring a dead past alive?

Answer in the Comment box below or on WhitmanWeb’s Facebook page.