Much of “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” records the search of the poet for a way to sing appropriately of the president’s death and the massive death of the war. He listens to a solitary unseen bird—a hermit thrush—that sings loudly what the poet hears as “death’s outlet song of life.” He is desperate to translate that bird’s “warble” into a “human song” and to use it as his own as he too seeks an “outlet” from the war’s carnage that seems to surround him. So he follows the bird’s call into “the swamps, the recesses,” where he finds himself walking with two spectral companions on either side of him—“the knowledge of death” and “the thought of death.” The swamp is the ultimate site of composting—the place where the liquid and the solid merge and meld, where the decay of death is at its most fertile, continually producing new life out of the muck, a landscape that embodies “death’s outlet song of life.” We all live continually with the “thought of death”—it walks with us during all the moments of our life—but none of us has the “knowledge of death.” If there is “knowledge” to be had, it can only come after death has occurred. So all of us walk suspended between the thought and knowledge of death. In the swamp, though, the poet begins translating the song of the solitary singer, the thrush’s song that is at once assuring and unsettling: death will come “sooner or later” “to all, to each,” but it is “lovely and soothing” and “cool-enfolding.” Death’s song is finally a “carol” sung “with joy.”

So, surrounded by the “swamp-perfume” and held close by the thought and knowledge of death, the poet for the first time allows himself to open his eyes fully to the horror of the Civil War he has experienced over the previous couple of years. In a remarkable unbinding of his sight, he allows his experiences of caring for a hundred-thousand sick, wounded, and dying young soldiers to tumble from his eyes deep into his brain, imagination, and perception. Up to now, he has kept his “sight . . . bound in my eyes,” but now the carnage flows into his mind unchecked, and his world shatters into fragments—we see “the staffs all splinter’d and broken,” like the broken staffs that make up the title page of his Drum-Taps sequel. And, as his sight opens up to the “battle-corpses, myriads of them, / And the white skeletons of young men,” he absorbs “the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war.” These are, as we saw earlier, the “million dead” that he can “sum up” but not “summon up”: they are already “debris,” part of the same landscape that Lincoln’s death train traveled through on its way to Springfield, Illinois, that Whitman described in Section 5 of the poem: “Amid lanes and through old woods, where lately the violets peep’d from the ground, spotting the gray debris. . . .” America’s lands are melded now with this “debris and debris” (even Whitman’s repetition of the word emphasizes its root meaning of “breaking apart,” as if simply saying the word leads to another breaking off of more debris).

The comfort for Whitman is that he now carries with him the knowledge from the thrush’s solitary song that one thing death is not is suffering: he knows that the dead “themselves were fully at rest, they suffer’d not.” It is “the living” who remain and suffer. The dead are beyond that concern—they know the “soothing” peace of death: we the living are the ones who carry the burden of suffering.

So the poem ends with the return of the participles (those verbs of continuing action) in a long chain of repetitions of the word “passing” (with its buried “sing”) as the poet now finds he can take the first steps of leaving behind all the things he has been occupied with in the poem—he passes the vision of the dead, the night, the song of the hermit thrush, the lilacs themselves. While other ongoing participles record persistent mourning (falling, flooding, sinking, fainting, warning, bursting), he can nonetheless begin to sense the “blooming, returning with spring,” the spring as faint sign of hope instead of reminder of immense loss.

But the poem does not end there. Like T. S. Eliot sixty years later in The Waste Land, Whitman leaves us with fragments that he is trying to shore against his ruin. For Whitman, those fragments are what he calls “retrievements out of the night,” the bits and pieces of the debris that he is able to hold onto for guidance and to shape into this poem—the evening star (Venus) that seemed so bright and low in those nights before the assassination of Lincoln, the bird that sang death’s outlet song, the aromatic lilac, the “comrades” that accompanied him in the swamp, the mass of “the dead I loved so well,” and the unnamed Lincoln himself (“the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands”).

In 1865, the final verse paragraph of the poem began “Yet each I keep, and all.” Whitman would later revise that opening to “Yet each to keep and all.” It’s a tiny change—from “I” to “to”—but it makes all the difference. As he imagines shoring up those precious “retrievements from the night,” pulling the fragments together to begin to create a future out of the debris, we realize with a sudden shock that Whitman’s delicate revision has transformed the final nine-line verse paragraph into a sentence fragment. He has removed the subject/actor (the “I”) and left the act of retrievement an infinitive verb (“to keep”), held forever in suspended animation, something hoped for but never achieved, never activated in time. A fragment.

—EF

Now while I sat in the day, and look'd forth,

In the close of the day, with its light, and the fields of

spring, and the farmer preparing his crops,

In the large unconscious scenery of my land, with its lakes

and forests,

In the heavenly aerial beauty, (after the perturb'd winds,

and the storms;)

Under the arching heavens of the afternoon swift passing,

and the voices of children and women,

The many-moving sea-tides,—and I saw the ships how they

sail'd,

And the summer approaching with richness, and the fields

all busy with labor,

And the infinite separate houses, how they all went on, each

with its meals and minutia of daily usages;

And the streets, how their throbbings throbb'd, and the cities

pent,—lo! then and there,

Falling among them all, and upon them all, enveloping me

with the rest,

Appear'd the cloud, appear'd the long black trail;

And I knew Death, its thought, and the sacred knowledge

of death.

Then with the knowledge of death as walking one side of

me,

And the thought of death close-walking the other side of me,

And I in the middle, as with companions, and as holding the

hands of companions,

I fled forth to the hiding receiving night, that talks not,

Down to the shores of the water, the path by the swamp in

the dimness,

To the solemn shadowy cedars, and ghostly pines so still.

And the singer so shy to the rest receiv'd me;

The gray-brown bird I know, receiv'd us comrades three;

And he sang what seem'd the song of death, and a verse for

him I love.

From deep secluded recesses,

From the fragrant cedars, and the ghostly pines so still,

Came the singing of the bird.

And the charm of the singing rapt me,

As I held, as if by their hands, my comrades in the night;

And the voice of my spirit tallied the song of the bird.

Come, lovely and soothing Death,

Undulate round the world, serenely arriving, arriving,

In the day, in the night, to all, to each,

Sooner or later, delicate Death.

Prais'd be the fathomless universe,

For life and joy, and for objects and knowledge curious;

And for love, sweet love—But praise! O praise and praise,

For the sure-enwinding arms of cool-enfolding Death.

Dark Mother, always gliding near, with soft feet,

Have none chanted for thee a chant of fullest welcome?

Then I chant it for thee—I glorify thee above all;

I bring thee a song that when thou must indeed come, come

unfalteringly.

Approach, encompassing Death—strong Deliveress!

When it is so—when thou hast taken them, I joyously sing

the dead,

Lost in the loving, floating ocean of thee,

Laved in the flood of thy bliss, O Death.

From me to thee glad serenades,

Dances for thee I propose, saluting thee—adornments and

feastings for thee;

And the sights of the open landscape, and the high-spread

sky, are fitting,

And life and the fields, and the huge and thoughtful night.

The night, in silence, under many a star;

The ocean shore, and the husky whispering wave, whose

voice I know;

And the soul turning to thee, O vast and well-veil'd Death,

And the body gratefully nestling close to thee.

Over the tree-tops I float thee a song!

Over the rising and sinking waves—over the myriad fields,

and the prairies wide;

Over the dense-pack'd cities all, and the teeming wharves

and ways,

I float this carol with joy, with joy to thee, O Death!

To the tally of my soul,

Loud and strong kept up the gray-brown bird,

With pure, deliberate notes, spreading, filling the night.

Loud in the pines and cedars dim,

Clear in the freshness moist, and the swamp-perfume;

And I with my comrades there in the night.

While my sight that was bound in my eyes unclosed,

As to long panoramas of visions.

I saw the vision of armies;

And I saw, as in noiseless dreams, hundreds of battle-flags;

Borne through the smoke of the battles, and pierc'd with

missiles, I saw them,

And carried hither and yon through the smoke, and torn

and bloody;

And at last but a few shreds of the flags left on the staffs,

(and all in silence,)

And the staffs all splinter'd and broken.

I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them,

And the white skeletons of young men—I saw them;

I saw the debris and debris of all dead soldiers;

But I saw they were not as was thought;

They themselves were fully at rest—they suffer'd not;

The living remain'd and suffer'd—the mother suffer'd,

And the wife and the child, and the musing comrade suf-

fer'd,

And the armies that remain'd suffer'd.

Passing the visions, passing the night;

Passing, unloosing the hold of my comrades' hands;

Passing the song of the hermit bird, and the tallying song

of my soul,

Victorious song, death's outlet song, (yet varying, ever-

altering song,

As low and wailing, yet clear the notes, rising and falling,

flooding the night,

Sadly sinking and fainting, as warning and warning, and

yet again bursting with joy,)

Covering the earth, and filling the spread of the heaven,

As that powerful psalm in the night I heard from recesses.

Must I leave thee, lilac with heart-shaped leaves?

Must I leave thee there in the door-yard, blooming, return-

ing with spring?

Must I pass from my song for thee;

From my gaze on thee in the west, fronting the west, com-

muning with thee,

O comrade lustrous, with silver face in the night?

Yet each I keep, and all;

The song, the wondrous chant of the gray-brown bird, I keep,

And the tallying chant, the echo arous'd in my soul, I keep,

With the lustrous and drooping star, with the countenance

full of woe;

With the lilac tall, and its blossoms of mastering odor;

Comrades mine, and I in the midst, and their memory ever

I keep—for the dead I loved so well;

For the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands…

and this for his dear sake;

Lilac and star and bird, twined with the chant of my soul,

With the holders holding my hand, nearing the call of the

bird,

There in the fragrant pines, and the cedars dusk and dim.

To the “trinity sure” in the opening section of “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d,” consisting of the lilac, the star, and “ever-returning spring” (soon to be replaced by the song of the thrush), Whitman adds a third triad: the speaker walking in the swamp with his boon companions, the thought of death and the knowledge of death, one he knows well and one he cannot know until he dies. The altar of his civic religion, we learn at the start of the last third of the poem, lies in “the hiding receiving night,” where the thrush “receiv’d us comrades three;/ And he sang what seem’d the song of death, and a verse for him I love.” Mortality is the key in which Whitman wrote from the first version of “Song of Myself” through the deathbed edition of Leaves of Grass, and nowhere is this more apparent than in his elegy for Lincoln, when “the voice of [his] spirit tallied the song of the bird,” tally in this instance meaning both to correspond and to calculate. The losses he tallied among the “ghostly pines,” personal and political, were enormous.

This song, which in the poet’s imagination has crossed the country as part of the president’s funeral procession, now brings him visions of the war—armies, shredded flags, broken staffs. And more: “I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them,/ And the white skeletons of young men—I saw them;/ I saw the debris and debris of all dead soldiers.” Their suffering is over, their knowledge of death complete, and so it falls to the living—mothers, wives and children, “the musing comrade” (the poet, that is)—to come to terms their losses. Impossible, of course. Which is why he is haunted by “the ever-altering song” of the thrush, a psalm rising from the swamp to flood the night, cover the earth, and fill the heavens: “death’s outlet song.” It changes key with each and every death.

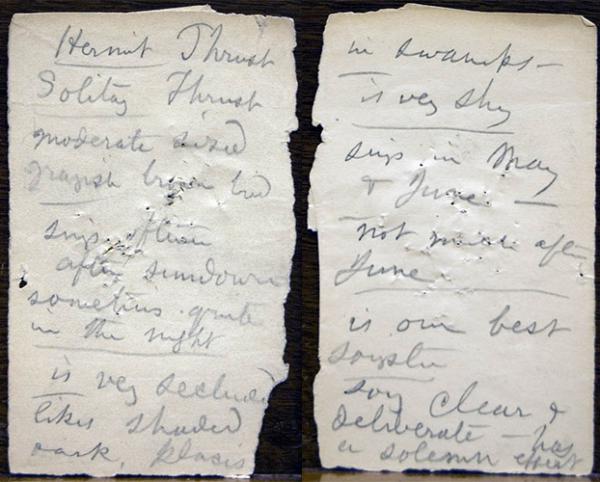

Among the usages cited in Merriam-Webster’s definition of the word keep, which appears four times in the final ten-line section of the poem, are: to keep a promise, to keep the Sabbath, to keep time, to keep us from harm, to keep a garden, to keep watch, and to keep a diary, all of which must have figured in Whitman’s thinking. (See his list of words relating to the thrush.) To have, to continue, to protect, to provide for, to honor or fulfill—these meanings no doubt echoed in his memory of his fallen comrades and Lincoln, “the sweetest, wisest soul of all my days and lands…” The last word is a surprise (we expect to hear nights), as death so often is. This death in particular would shape the lands anew, as the war itself had already done. In the dictionary we learn that the keep was the strongest part of a medieval castle. The same holds for Whitman’s poem.

—CM

Style is important. When we want to capture a sense of fragmentation and loss in our writing, it may be effective to use the syntax as well as the words to communicate the feeling of brokenness, as Whitman does at the end of his revision of “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d.” Write a brief paragraph that recalls a moment you felt broken and lost, and use syntax as well as diction to capture the feeling.

Answer in the Comment box below or on WhitmanWeb’s Facebook page.