Music in an Unsafe America

Last Saturday, Paul McCartney took a sip from a paper cup. His owl’s head had grown older, but the high round eyebrows expressed the same surprise as in the past. He yelled something cheerful to the men in uniform in the front rows, stepped up to the microphone and said: ‘Yesterday.’ For a moment, silence. Then: ‘All my troubles seemed so far away.’ The audience erupted into a sound that resembled most a collective gasp of amazement. The favorite song of the past century appeared suddenly to have been written especially for this occasion.

In a city where people go to the shrink like we visit the supermarket, trauma relief is in full swing, both collectively and individually. The great songs of pop music work on both levels. In daily life, they have been reduced to elevator music and youth hostel repertoire. At a time of crisis they rise to new meaning. Precisely because we know them through and through, because they belong to the atmosphere of western society, they provide people with a refuge for their most individual sorrow, while at the same time giving them the feeling that they are not alone, that they belong to a greater community. At last Saturday’s Concert for New York, which I watched on the quiet third floor of Iowa House, ‘Yesterday’ was a kind of national anthem and at the same time a lonely contemplation of someone lost. Over the past few weeks, the same went for ‘Bridge over troubled water’, ‘Fire and Rain’ and, of course, John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’.

Songs like that were conceived in another age, but they open up now that a new moment requests them to, and they prove able to shelter and surround this moment, as if they already carried the sadness of today within themselves. In its hour of tragedy, America finds that the past decade of unhindered cultural globalization hasn’t produced suitable anthems. Instead, it has reclaimed the songs it sent out into the world during the years of Vietnam and the Cold War. These are songs from a time when rock music and protest movement were synonymous. Alternative and establishment were separate worlds. Now they are being sung in memory of fallen police officers and firemen. And that memory is being celebrated. Since the stunned first days after the attack, survivors in their collective mourning rituals have started cheering the dead, the missing and themselves. There they were, last Saturday, in Madison Square Garden, hugging each other, singing along with the music, dancing and shaking, waving the photographs of their dead buddies, with tears in their eyes.

On stage, you could see Mick Jagger, who once sang ‘Streetfighting Man’; Roger Daltrey, of ‘My Generation’; and Eric Clapton, who once did a nice cover version of ‘I shot the sheriff.’ The rebels of days gone by were cheering the police, and the police were cheering the rebels. Many of the artists wore police caps, the old symbol of power and abuse of power. After five nervewrecking weeks, New York needs heroes, and they choose the people who make sure that old securities remain in place: be it buildings, songs or the law.

The power struggles of twenty or thirty years ago are forgiven and forgotten. September 11 has meant a rehabilitation for the old authorities. Never before have a governor and a mayor been so passionately received at a music event as Pataki and Giuliani last Saturday. The generation of fifty-somethings in politics and rock music stands united. The attacks have left very little room for dissent, even in the traditional counterculture of pop music.

That’s why the final chorus of such an event is always a relief to watch. They are meant to project complete unity and harmony, and they achieve exactly the opposite. Saturday, when Paul McCartney sat down at the piano and hit the first notes of ‘Let It Be’, a wave of endearment and brotherhood swept through the audience. On stage, all the artists gathered one more time. The harmony singing was, as usual, terrible. Wandering across the huge stage, looking for an available microphone, the stars suddenly looked very human. Sometimes they ended up in unexpected two’s and threes, not completely sure about the company around them. Pete Townsend kept returning to Sir Paul’s mike, as if he had something urgent to say. But what? We’ll never know. The heroes were mortal individuals again. They got lost in the noise. And it was only then, in the confusion of a party that never became a celebration, that they turned into a precise reflection of New York, a city where the survivors stagger around in a daze and the dead are still very present among them.

October 2001

-

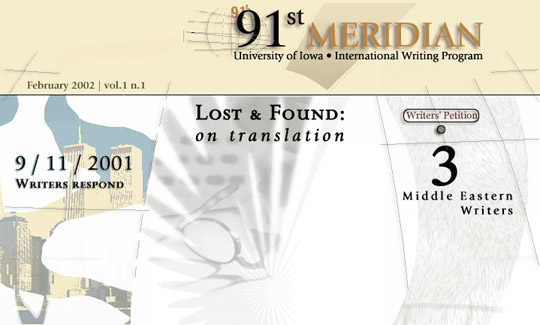

9/11/2001: Writers Respond

- Torunn Borge, Too Little Seen

- Joy Goswami, Headless Torso

- Christopher Merrill, The Hour of Lead

- Chris Keulemans, Music in an Unsafe America

- Man-sik Lee, The Urgent Need

-

Lost and Found: On Translation

- Writers' Petition

-

Middle Eastern Writers