Four "Sonnets to Orpheus" in new translation

Revisiting "the essential mystery" of Rilke's poetry

Translator's preface:

To translate Rilke, one must learn how to dance the lyric shape and pulse of his poems. With his “Sonnets to Orpheus,” this is a unique challenge, since this collection represents nothing short of a reinvention of the sonnet form. Here, the music and movement of language—the dance, as it were—is what is essential to this task, and at the same time most elusive. And, if translating lyric poetry is, in general, an “extreme” art, the complex and often broken diction together with the unyielding lyricism of this poet’s language raises the stakes even higher: Rilke intends these poems, as with Orpheus’s playing for Eurydice, to seduce us, to lead us forth from the shadows of despondence or despair. The translator must dare to bend and sometimes break grammatical rules and the logic of syntax in order to evoke a musicality Rilke is so intent on rendering for us.

Translations of these sonnets must also find the means of enticing and provoking readers in the “new” language, as they do in Rilke’s German. An essential part of their seduction has to do with a form that might be as confusing to the mind as it is exquisite to the ear. A translation that attempts to clarify these sonnets’ obscurities, to “fix” their jagged diction, might make for good (English) poetry, but it will not allow us to experience something of their essential mystery in the original. Yet recreating something of the puzzlement and surprise found in these sonnets calls the translator to be as inventive and even adventurous with her English as Rilke was with his German. This is what makes the “dance” so intriguing, and at the same time so demanding. As with dancing, success has here as much to do with technical competence as it does with artistic savvy.

--Mark S. Burrows

I.1

Up rose a tree. O pure uprising!

O Orpheus singing! O towering tree in our ears!

And all kept silent. But even in this solitude,

a new beginning,sign,and change came forth.

Creatures thronged out of the stillness,out of

the spacious forest, uncluttered of lair and nest;

and they were so still in themselves,

not from cunning and not from fear

but from listening. Bellows, cries, commotion

seemed distant from their hearts. And where

not even a hut existed to receive them—

a shelter made of darkest desiring

with an entrance whose jambs trembled—

you built for them a temple for their hearing.

I.3

A god could do it. But tell me this: how can anyone

follow him by passing through the narrow lyre?

Our minds are divided;at the crossing of two

heart-paths,one finds no temple to Apollo.

Song, as you teach it, is not about desire,

and does not court what might ultimately be attained.

Song is being. Something simple for the god.

But when finally are we to be? And when will he

turn the earth and the stars toward us?

It isn’t this, youngster, which makes you love,even when

the voice forces open its mouth for you. Learn

to forget that you sang out. This passes away.

But to sing in truth is a different breath.

A breath around nothing. A blowing in god. A wind.

I.22

We are the achievers.

But this march of time,

consider it as nothing

among what endures.

All that hurries

will soon be done;

and what lingers

initiates us.

O, youth, don’t waste

your courage on speed,

or squander it in flight.

Everything is at rest:

darkness and bright,

blossom and book.

I.23

O,only then when flight

no longer rises for its own sake

into the solitude of skies,

sufficient unto itself

as happens with brilliant designs—

like a tool that was able to

play the part of one favored by winds,

confident, agile, and fit—

then, when a pure tendency

of proliferating machines

eclipses boyhood pride,

will the one driven by the will to win,

the one who conquered the distances,

be what he alone gained in flying.

Mark S. Burrows is professor of Religion and Literature at the University of Applied Sciences in Bochum, Germany. His recent publications include two volumes of translations from the German: R.M. Rilke’s Prayers of a Young Poet, and the German-Iranian poet SAID’s 99 Psalms. A collection of his poems, The Chance of Home, will appear in 2015. He serves as poetry editor for Spiritus.

8.1 Spring 2015

Editorial

The postcard

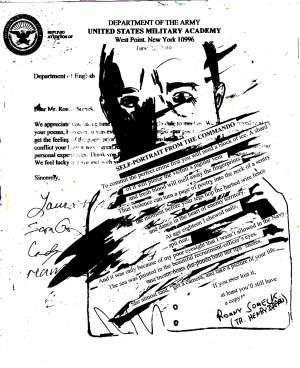

- Ronny SOMECK / Self-Portrait of the Commando

Fiction

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Blindfolded and bound in the boot of an unmarked police car, the boy was delivered to the House of Stories...

- Marie-Louise Bibish MUMBU / Me and My Hair

The Bana mboka, the kids from here, versus the Diaspora, those who banished themselves. Fresh-Bagged versus The Bottled Stuff. Rainy Season versus Winter. Stayed versus Left. On Foot versus Driving. Boubou against Low-Waisted Pants...

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Poetry

- Ariane Dreyfus translated from the French by Corinne Noirot + Elias Simpson

- R. M. Rilke in new translations by Mark S. Burrows

- Shah Hussein and Naveed Alam in a Punjabi-English dialogue. With a preface, and an interview conducted by Spring Ulmer

Non-Fiction

- Michael Zeller / India. Walking. Translated from the German by Joseph Swann

- Sadek Mohammed (Iraq), Boaz Gaon (Israel), Mujib Mehrdad (Afghanistan) on writing in a country at war

Book review