Manuel Becerra, ": Note recorded in 1990"

Manuel BECERRA is the author of six books of poetry, including Instrucciones para matar un caballo [Instructions for Killing a Horse] (2013). A winner of six national poetry awards, he has had fellowships from the Foundation for Mexican Letters, the Mexico City Institute of Culture, and Art Omi in upstate New York.

TRANSLATOR'S NOTE

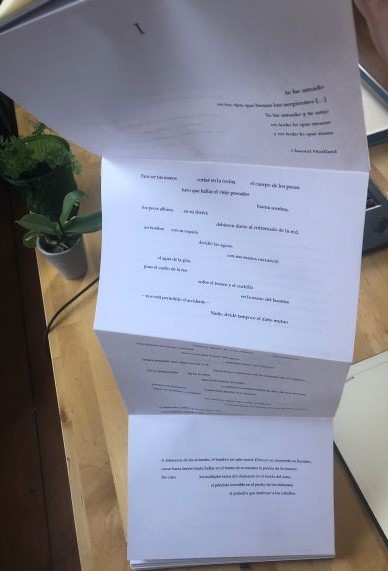

This poem comes from the collection Writings on the Other Animals, forthcoming from the Song Bridge Project. A special edition will be printed as the author intended: on one long sheet of paper and folded accordion-style into a book. According to Becerra, this format is essential, as the book is like a river: one could start or finish at any point in the book, just as the shore of a river could be the end or the beginning of a journey. As Henry David Thoreau said, "Music is continuous; only listening is intermittent." Writings on the Other Animals uses the combination of art object and art text to transcend the linearity of time--a theme echoed within and across several poems in the collection. The format calls attention not only to the final product, but to the act of writing, the act of reading, and the spaces where these acts take place. Becerra adds, "The book's format responds to the interior need of the poems that comprise it: the flow, the rhythm, the importance of the book as an object in the face of the brutal ephemerality of technology." The image below shows a copy of the book designed by María Carolina Ceballos, an MFA candidate in Book Arts.

In this particular poem, which is based on a childhood story, I had a decision to make about the pronouns referring to the dog. I saw the possibility of highlighting the boy’s relationship to the dog with a change from “it” to “him.” I chose to use “it” to refer to the dog at the beginning to accentuate the emotional distance the boy feels toward the dog at first, a time when another child with another dog might be filled with enthusiasm and warmth. I started using “he/him” pronouns for the dog after the second time the boy says “I got a dog.” After this statement, he says he thought about the dog every time it rained, which shows that a tenderness grew; the narrator is now reflecting on this dog with love. By the end of the poem, instead of emotional distance, the boy is lamenting the physical distance created by the father abandoning the dog and driving off.

--Kathleen Archer

: Note recorded in 1990

when I was little, I got a dog / a sinister one, and at night / in the light of the moon / it changed the color of its fur. / Resentful, I watched it / breathing as it slept its evil sleep. / When I was little, I got a dog raised by vagabonds. / I pushed some food toward it one morning / and that morning, in one bite / it sank its dirty and foul-smelling little jaw / into the palm of my hand. / I thought about hurling stones at it and at my father / who paid for its dark palate / --supposed indication of good breeding-- / one drunken night. / I got a dog when I was six. / I thought about him whenever it rained: / his little wooden house in the thunder. / One night my father took my dog in the car, / far away, where his sense of smell would be lost / among the markets and in the shadows, / but that night he kept running / after us, and still keeps on / --Isn’t that so, Father?-- / running and gets tired and once more loses / height in the distance / until disappearing again.

Kathleen Archer translates from French and Spanish. She holds an MFA in literary translation from the University of Iowa.

FALL 2020 vol 10 no 4

Non-fiction

"The Pleasures of Pestilence" by Carlos Gamerro, translated by Ian Barnett

"Cirrus" by Thawda Aye Lei, translated by author with Kaylee Lockett

Excerpt from Book of Tremors by Jacqueline Goldberg, in Bill Blair's translation

Poetry

Three Poems by Tautvyda Marcinkevičiūtė, in Caroline Froh's translation

": Note Recorded in 1990" by Manuel Becerra, in Kathleen Archer's translation

"Lonesome Hearts' War" by Marius Ianus, in Liviu Martinescu's translation

Fiction

"The Little Watermelon Seed" by Hajar Bali, In Keenan Walsh's translation

"My Father, the Scafista" by Djarah Kan, in Julia Conrad's translation

Book Review

Daniel Simon, ed. Dispatches from the Republic of Letters , reviewed by Jan Steyn