"The Last Bird Burial Master"

The fiction writer, poet, essayist and journalist Van Cam Hai was born in Quang Binh, Viet Nam, in 1972. He is a member of the VietNam Association of Writers and of the Vietnamese Association of Journalists. His work has been translated into Chinese as well as English, and appeared in publications that include Tinfish, The Literary Review, and the anthologies Vietnam Inside-Out: Dialogues and Three Vietnamese Poets. “The Last Bird Burial Master” is extracted from his 2004 collection Tibet- Blooms Drop In the Sunshine.

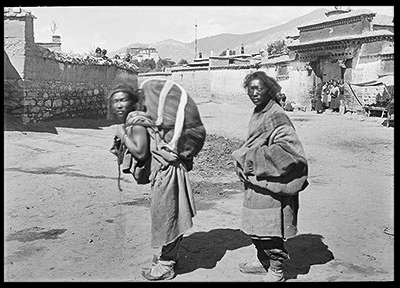

I had been to many spiritual places in the world but Tibet always has a solemn position in my pinnacle of respectability. In Tibet, I found myself as a wandering baby within the magic of Tantric Buddhism, falling in line with brilliant nature. I was very happy to meet Rigpaba and to learn about the religious significance of the burial bird–a wild custom to western people. It was a wonderful experience. I was the first Vietnamese writer to visit there alone in 2003. Don’t be afraid of anything! Allow yourself to discover the mysterious parts of the world! Let’s go, and see, and have a heart to heart with humankind, with the mind of a spiritual soldier. As the Tibetan said, be a humanitarian. That is the message of my story.

-- Van Cam Hai

Translated from the Vietnamese by Van Cam Hai and Lauren Shapiro

I did not know as I entered the butter tea shop beside the gate of Jorkang pagoda that I would meet there a secretive man whose profession would shock the outside world. This man’s job was to honor the age-old Tibetan custom of “celestial burial,” which is also known as “bird burial” or “sky -burial,” the sacred funerary ritual in which a corpse is sliced to pieces and thrown to the mouths of vultures.

There was no music in the tea shop in Lhasa. All feeling seemed to relax into the purple fabric lining of the chairs; customers leisurely drank their tea. The world here was as plain as the low tables, and the lives of the people were bowls of butter tea. They drank tea as though they daily drained their lives.

I thought of using the restroom as I waited for the tea to steep, but the idea of the wet toilet sheltered only by a sheet of fabric in the cold street made me pause. The door frames in Tibet are draped with fine cloth rather than wood as it shades the rooms from cold winds ,being decorated ornately. At last I asked an old man for directions. Passing by the many small rooms of the tea shop, my frostbitten footsteps pitched against the stone floor.

On the walls of the tea shop the light from the lively colors of a thanka painting made me shiver. The painting showed a man swinging a sword through a dead body. The face of the headsman was strangely still and focused on the motion of slicing, while the face of the corpse was smiling. Behind the headsman was a flock of birds with long beaks filled with fresh blood. The movement of the sword swooping down as it sliced feet stopped me in my tracks. I realized that behind me the old man was looking at me and at the painting.

“It’s me,” he whispered. Though his voice showed his age it still shone with an odd joy. “The man swinging the sword is me.”

“You made a painting of an executioner? You are fond of that practice?”

“No, I am not an executioner. I am the last celestial burial master left in Lhasa.”

“Are you ?” I cried out in the dim room. “Really?”

Without answering, the old man stepped forward and touched the painting wistfully. From the corners of his eyes, tears seemed brimming. In front of me is a celestial burial master , I thought—a man who conducts the most imposing and frightening funeral in the eyes of the world.

On the way to Tibet, I had many thoughts of what might occur on the trip, but I had never dreamt of meeting a celestial burial master, a legend that I had assumed was imaginary. I trembled returning to the table and ordered two full bowls of tea. On my invitation, the old man stepped toward the table. His eyes glinted sharply, and for an instant I felt he was walking toward my body as toward a corpse. I looked silently at his ten fingers, gnarled from holding the tea bowl. Those two hands and the bloodstream that coursed through them had once been skilled at slicing bodies.

“In the painting, do I seem alive?” asked the old man.

“Alive, yes, very alive.”

The Celestial Burial was the sacred funeral rite of Tibet. Foreigners like you may find it barbaric, but for Tibetans it was a high art.”

“Yes, the art of freedom,” I answered, hoping not to miss this opportunity. “Could you tell me about it?”

“I’ll tell you; I’ll also show you.”

The old man stood up, walked quickly to an apartment building next door, then returned to the table. Outside, the sun shone but my body felt like a block of ice rolling from the Himalayas down to the tea shop. In his hands was a sharp sword with a curved blade. Though not as shocking as the three-pronged dorje hatchet used in many Tantric Buddhism rituals, the old man clutched the lancet tightly, and his assassin pose was terrifying.

“I am not as old as I seem.” His withered arm swung the lancet in a ray of light. Not daring to look at him, the customers left their chairs in succession. “Speaking plainly, even if I were blind I could slice the flesh on your body into perfect pieces.”

He seemed as peaceful as a child—perhaps as he had been in Mon Ngung, where he was born some ninety years ago. After his birth, Rigpaba’s parents were pleased when an astrologer foretold that he would become a Lama doctor of the Mon Ba Tribe. Provenant from Mon Ngung, the Mon Ba tribe live scattered in different districts—Mac Thoat, Lam Chi, Tho Na in South Tibet. Rigpaba’s parents, like others in Mon Ngung, were poor and earned their living by farming, breeding, and hunting. Anyone in their situation would have been thrilled for such an opportunity.

At the age of six, Rigpaba was sent to the abbey. After the day a curl of his hair was returned to his parents as proof that he had been accepted for instruction to become a Lama, his parents and friends were forbidden to see him for twenty-six years. Overcoming many trials, Rigpaba completed the first five levels of teaching. First, he was a hermit serving in the abbey, then he became a sadi, receiving the holy orders of thirty-six articles of law, then a ti kheo receiving 150 articles of law, then a gheshe – a doctor of Buddhology, a master in Buddha law, Abhidharma, Brahman bible, and nothingness philosophy. Stepping across the threshold of Theravada and Mahayana, Rigpaba was taught the sacrament of the secret discipline of Mat Tong, and finally became an outstanding gyupa, one who is taught through mind transmission. At that time Rigpaba became a Lama –an official hermit. In addition to the dogmas and his practicing of experimental mind transmission, Rigpaba had to study methods of curing diseases and guiding the dead to the other world. Though he never returned to his hometown, Lama Rigpaba had visited remote mountains and little-known places to search for natural medicine unknown to most people. The early morning when, in his role as a monk, he first helped the undertaker team to carry a corpse to the mountain altered his religious life forever.

•••

The tiger’s growl and the nameless flowers on Yarlung Tsangpo abyss are falling down endlessly in the brightly-lit stab of Rigpaba’s memory. The first time I remember being conscious of sorrow was a lonely evening when I was left alone with a colony of ants. Being the youngest child, I liked to play with the ants when asked to keep an eye on the house. Black ants, red ants, brown ants relentlessly moved heaven and earth to carry food to their burrow. They were a fragile strand of life linking rice to nest. The strand would be broken if even one was killed, and the ants would become momentarily confused before gathering to bring the corpse home. I became conscious of death from those solitary days spent with the ants, though I did not yet understand completely how humans dealt with their death. I wondered how ants handled their corpses in those dark holes. Did they eat the corpse or bury it as human might? If they buried it, was it high on a hill or deep in some dank place?

My grandmother died during a cold winter in 1981. Never have I seen my mother cry so much. She cried not only out of love but out of sympathy because my grandmother had given birth to two daughters and no sons; my grandfather had never forgiven her for this. She cried because my grandmother died in a flood, and she could not carry her body across the river to be buried in the mountain, but had to bury her in a sandbank at the end of the village. In Vietnam, my childhood was made up of days running errands and standing at the roots of the banyan tree to see off the deaths of the village across Nhat Le River. In parting with their deceased, the families living on the riverbank had to carry the coffin around the village, and then to the landing. When my grandfather died, his coffin was brought to each hamlet before being carried across the river to the mountain.

When funerals are performed, Nhat Le River becomes a stage. To carry the coffin, the tombstone, and the relatives, people tie boats together into a raft. Even if the waves are rough, the raft is first rowed some rounds near shore so that the first son can give thanks to the villagers standing there.

There are rivers in Tibet, but there is no wood to make boats, and no one dares to use only cowhide in those deep abysses. The only way to dispose of the corpse is to bury it on the spot. However, because the land is so hard, other forms of burial came into being: the most common are bird-burial, cremation, and water-burial. The burial rites differed among tribes. While the Mon Ba and Lac Ba tribes used all three burial customs, the Dang tribe banned water-burial because they believed sinking a corpse in water would bring disasters to the family of the deceased.

In the Tibetan language, the human body is “tu”—something we leave behind. A human is only a traveler who dwells in the body for a short time. Tibetans do not care to enrich their lives with material objects. For them, a plain house, a little tsampa flour , and some goat dung to light a fire in the cold winter are enough. On thousand-meter high passes houses appear drifting on snow. It seems they want to separate themselves from this world. Because the body is just a material sack to house the soul, death means nothing. And, on this cold plateau, where the blue sky and glaring light are everywhere, nothing could be more beautiful than burying the dead in the world of light. This notion inspired the customs of bird burial. What a sublime idea: the body, rather than being discarded, is instead enshrouded by light!

In order to send a corpse to the world of light, birds must bring it high into the sky. The stomachs of these birds become a living coffin flying in immense space. In order to lay the corpse in those small coffins, it must be sliced into tiny pieces. Such work is only for those with thick skin.

In Tibet, the masters of the Celestial Burial lived and worked in isolation; they were of a world apart. They spoke only to the world of death. From their bodies, dark air emanated and gathered. They were not like the Vietnamese undertakers whose job is simply to carry the coffin when attending a funeral.

The masters of the celestial burial would wait three nights and three days, until the body had died completely and the soul had left through the teachings of Bardo Thodol, a holy book written by a Buddhist monk in the 8th century. Roughly translated it means The Book of the Dead, as there is no verb in the Tibetan language meaning “to die.” After those three days, the master’s team would bundle the corpse into a piece of cloth and carry it to a distant place where no one dared to approach.

When the corpse was fastened to four poles, the master began to make their autopsy. Each stab was exact. The slices were made in extreme precision again and again until the corpse was just a skeleton. As the pieces of flesh flew off the lancet, the flock of vultures welcomed it, not allowing a blood drop to fall. The largest of the flock enjoyed the heart, and others in turn ate to the last piece of meat. When the flesh was gone, the skeleton too was pulped, which they mixed with tsampa wine for the vultures to bring to the sky.

The master were not only concerned with the funeral; they had to slice carefully because during their grisly performance they also studied the causes of death. In the Western world, autopsy is a relatively recent phenomenon due to the strict laws of the church. Yet it has been an everyday affair in Tibet for thousands of years, though it originally developed more as an offshoot than as a principal aim of the method of celestial burial.

After following this team for more than a year, Rigpaba became an experienced dissector. His swipes were as fast as a flash of lighting, more precise than a ruler’s, more sophisticated than an averager’s . Through his work the causes of death were quickly revealed. Then one day he suddenly took leave of the monk’s robe to become a professional celestial burial master.

“One early morning, I followed the team to slice a corpse as usual,” Rigpaba explained, and his eyes seemed to see the past through a flickering ray. “I didn’t know why I felt mournful at the first stab. Then, at the time I brought down the lancet, a cry shot out from the body. He advised me to slice him peacefully, not to tremble, not to grieve. The more finely I sliced, the faster he could go to the heavens! My god! It turned out that he was not dead yet!

“The stab must have awakened him! The whole team plunged forward to detach him from the poles but his body refused to move. He hurriedly uttered word after word to me. He knew it was time to die, and he asked me to slice his corpse devotedly, to slice until he became only nothingness.”

Rigpaba had collapsed on to the table for he knew that the man near death was an anonymous monk. Those words were no more than an instruction in dogma, a test to verify Rigpaba’s strength of spirit. Twenty-six years had come to nothing for him! Twenty-six years of religious training had crumbled under the word of death.

After that frightening morning, more than 500 corpses were sent to the blue sky by the executioner Rigpaba. He became as skilled as if a dancer on the corpse. His refined swing became a play that fascinated anyone who witnessed it. Even vultures were not fast enough to snatch all the pieces of flesh flying from the corpse like cherry blossoms dropping in a spring wind.

•••

Rigpaba sits silently. The cup of butter tea is empty. His eyes throw intangible stabs hovering over my body. Here is heart and life, here is meditation, here are pains persecuting me and Rigpaba. Not only Rigpaba, but now I too am a slicer, a young celestial burial master investigating the body of Rigpaba, drawing sharp cuts. In front of me, Rigpaba is now a corpse and perhaps from now on everyone will become a corpse to me, their bodies opening up the windows to their spirits.

Rigpaba sits silently. The cup of butter tea is empty. His eyes throw intangible stabs hovering over my body. Here is heart and life, here is meditation, here are pains persecuting me and Rigpaba. Not only Rigpaba, but now I too am a slicer, a young celestial burial master investigating the body of Rigpaba, drawing sharp cuts. In front of me, Rigpaba is now a corpse and perhaps from now on everyone will become a corpse to me, their bodies opening up the windows to their spirits. For Tibetans, all behavior must correspond to the circulating rhythm of the universe. Even the most trivial actions are checked carefully by the consciousness to determine how they mix with their surroundings. A situation might not seem positive at first; it becomes so in a larger context. When raising a cup of tea, it is not right to empty it in one gulp. Tibetans drink tea in mouthfuls, gradually and add more hot water before taking another sip. So, too, Tibetans will be offended if their guest does not drink a glass of wine slowly in three sips. Tsampa wine, made from barley flour with tea and yak butter or milk, can be found almost anywhere; people of all ages drink tsampa. To drink a bowl of wine, the guest should take one sip and wait to take the second until the host adds more wine. The third sip should be drunk in the same way. After three sips of wine, you have won the heart of your host.

One day, a young married woman went to ask Buddha how to practice mediation. Buddha did not teach her anything difficult. He looked at her two hands which were hardened from pulling water up from the well, and answered:

“You should concentrate on pulling water. Each movement must be made in clear thought. If you can do that, you will surely find your mind peaceful, delicate, and lucid. That is the practice of mediation.” The young woman awakened. She came back home, acted on Buddha’s advice, and found peace.

Rigpaba does not pull water up from the well as the young woman did. Rigpaba uses the sword as a method of discovering the Nothingness in his spirit. As he said, slicing a corpse means uncovering death. Life is hidden in the body, even the skeleton is given to the stomachs of vultures and disappears in the blue sky. All will be restful and completed naturally by the gesture of Thekchod! Thekchod is one of the two practices in the Tantric Buddhism book Nyingma dogma. It is the definitive action of cutting the ties of reason and sentiment, of breaking the barrier that prevents humans from approaching the freedom that by nature exists in the mind.

When Rigpaba brandishes the sword, he cuts the ties that hinder body, language, and mind from accepting the Buddhist teachings. He embraces those things born from the mind and the heart unhindered, like clouds in the sky. When we have understood these phenomena, that is the essence of Nothingness. We can enter into meditation, deep into religious contemplation. The teachings of the Buddhist priest Garab Porje were brought to life through Rigpaba’s slicing of the corpse.

When Rigpaba brandishes the sword, he cuts the ties that hinder body, language, and mind from accepting the Buddhist teachings. He embraces those things born from the mind and the heart unhindered, like clouds in the sky. When we have understood these phenomena, that is the essence of Nothingness. We can enter into meditation, deep into religious contemplation. The teachings of the Buddhist priest Garab Porje were brought to life through Rigpaba’s slicing of the corpse.

I spoke then. “On a snowy night in the Netherlands, watching a film about the Dalai Lama living in exile, I could not have expected to one day be downtown, in Octagonal Street, which had once been filled with blood and gun smoke. The footsteps of Buddhist priests squelched in the blood of Tibetans who died in this street. Nowadays, there is no longer the sound of gunshots in Tibet. However, in front of the Potala palace, at the foot of the peaceful Tibetan monument, there is always a Chinese soldier on watch with an AK gun in his hands.”

“They prohibited bird-burial. The celestial burial master’s team separated. All of them died. I am the last one here, longing for it.” Rigpaba seemed intensely regretful.

“And are you no longer practicing Zen meditation?” I asked cryptically, sharing in his sorrow.

“No, I still do!” Rigpaba’s eyes suddenly flashed. “How did you know the celestial burial is a method of practicing mediation? A secret of my life. Who told you?”

“Thekchod!” I answered mysteriously.

“Thekchod?” Rigpaba again drew the sword. The afternoon in Lhasa was transparent. The butter tea shop was empty. I could hear breath emanating from the whole body of the withered Rigpaba.

“You are worthy of being shown something.” Rigpaba stood and walked back to his apartment, which bordered the tea shop. I followed. Many candles were lit. In the room danced hundreds of thanka paintings. I was excited by the innumerable dances of the whirling sword which were painted sometimes in peaceful colors and sometimes in frightening, violent ones.

I had spent a long time immersed in the colors of Picasso’s cubist paintings in the cellar of the La Haye museum. I had also spent time passionately deep in the space of Van Gogh’s paintings in the Amsterdam museum, and had wandered in the world of many colors in the Louvre in Paris. However, never before had my thoughts wheeled so, as if boats were being warped by waves in the apartment of the thanka paintings. Here, I could see the image of Genie Yidam Yamankata holding in his hands a human skull full of blood. The genie of death is so ferocious that Tibetans cover the image of his face with cloth. I was puzzled by the natural beauty of a nude Tibetan girl. And I paid respect to the painful faces of Buddha which were expressed with different colors--white, red, green, yellow. All are facing the man brandishing the bloody lancet and flying with a flock of vultures into the blue sky. That is Rigpaba. Rigpaba is still practicing Buddhist contemplation in those thanka paintings.

In Tibetan abbeys, there are many works of art that are the product of an association of high-ranking Lamas. Under the instruction of a Lama master other Lamas will bring their thoughts together to finish their part of the painting. The assemblage of these parts makes a beautiful work of art. While painting, all the Lamas are in the state of Samadhi- Buddhist contemplation—reciting the Buddhist scriptures. Because the colors they use manifest something outside of themselves, all the lines of the painting gathered from different painters look to be from one hand. Rigpaba, a Lama doctor, an master of celestial burial, a Lama artist—did he paint alone or with others? How could he make such a formidable painting, one that seemed to hypnotize my every thought?

“I painted it by myself,” Rigpaba saw through my thoughts. “I did it after I gave up the sword. I painted my happier days. I have had nothing but painting for forty years.” The paintings were hypnotizing. I looked attentively and found that however new or old they appeared to be, the lines and colors all seemed essential and alive. The more I looked at them, the more lively and new the paintings appeared to be. The man whirling the sword in the new painting was even faster and more adventurous than the man in the painting of forty years ago. Thodgal! My self-confidence was like a candle’s light waxing in the face of Rigpaba.

“Thodgal!” While I was saying the word, I felt the sword looping around my back. I was suddenly too weak even to lift a rice bowl; how could I avoid his slice of precision? But no! Instead of receiving his sword, my whole body vibrated in the arms of Rigpaba!

“Thodgal!Tho-d-g-al!” His sounds were gradually sinking into his blood-vessels. The days of whirling the lancet, for him, had been the time of practicing Thekchod, and the days of painting were the time of practicing Thodgal. A part of Nyingma dogma, Thodgal means ‘direct’ in an urgent move, an instant change from here to there without the intervention of time. Thodgal is the highest form of meditation, both the simplest and the most difficult; it is sang-pa, the visible surpassing consciousness. Thodgal is the integration into the visible, the natural completeness of the tranquil base of self in Thekchod. The process from Thekchod to Thodgal is also the mean of verifying Dzogchen dogma— or “Great Perfection” that Palmasambhava, the great hermit, left for the Tantric Buddhism.

“Stay here! Stay here in Tibet.” Rigpaba hasn’t left the sword. I will teach you how to use this, how to paint Thanka, and how to drink three bowls of tea with tsampa cake. And when I die, you will be the one who offers me the slicing so that my body will fly away into the sky in the stomach of a flock of vultures.”

I silently listened to him as a little boy listening to his grandfather.

“I know you can’t stay. But I will offer you this sword. Take it to your homeland, not to slice corpses but to remember that wherever you are in your daily life, even in the corner of the kitchen, Thekchod and Thodgal live if you have a good heart.”

I was moved. I shivered. My fingers became anemic and pale. Holding the sword meant holding the free wings of the sky, holding the frightening but holy life of an Âm Công, holding a great seal of the secret discipline of Tantric Buddhism.

I left the tea shop. The sun was immense. People were rushing through Octagonal Street. No one knew that in Lhasa, there was a Master of celestial burial hiding, leading a private religious life with miraculous thanka paintings.

When leaving Tibet, the customs officers in the Lhasa airport wouldn’t let me bring the sword back to Vietnam. I had to ask my friend Hong in security to send it to me by special delivery. Thirty days later it arrived. During my trip home from the post office, no one knew it was the sword of a Tibetan celestial burial master, the weapon used in the custom of bird-burial famous all over the world.

Rigpaba, the old ant! I know that in the nest ants devote everything to life, so their deaths hold little importance. In the corner of Lhasa, Rigpaba will die, and his body will not be sliced into pieces. After a life devoted to training, his rough body of ninety years will shrink to dissolve in the immortal light that Tibetans describe as “melting into the body of the rainbow.” Will anyone have the heart to pick up the hair and fingernails that Rigpaba leaves behind as holy relics in the apartment filled with thanka paintings, or will they disappear swept under the some soldiers?

Translated from the Vietnamese by Van Cam Hai and Lauren Shapiro

Lauren Shapiro is a recent graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Her poems have appeared in POOL, Passages North, and 32 Poems, and she has translated and co-translated work from Italian, Spanish, Vietnamese, and Arabic into English. Currently, she is an assistant professor at Herzing College in Madison, Wisconsin, where she lives with her boyfriend Kevin and their dog Maddy.

6.1 Spring 2008

- Editorial

-

SPECIAL SECTION: NON-FICTION NOW

-

A MALAYSIAN BOOKSHELF

-

VAN CAM HAI

-

LAWRENCE PUN

-

PUJA BIRLA