Shrilal Shukla :: At This Age

From the Hindi--

A life-long civil servant, Hindi novelist Shrilal Shukla (1925-2011) was noted for his satire. His work reflects a deep involvement in government bureaucracy, and detailed knowledge of village life in Hindi-speaking north India. Most noted for his epic Raag Darbari, in which he lampoons the notion of India’s villages as a utopian refuge for the pure of heart, he published over twenty-five volumes, including novels, collections of short stories, and satirical essays.

Translator’s Note:

This story showcases Shukla’s biting satire—in this case directed at a narrator very like himself—a smug, elderly satirist, slouching toward death. After writing a witty essay about increasing attendance at one’s own funeral procession, the author encounters an elderly man who seems to wander about with a death wish and not much interest leaving behind a legacy. "At this Age" was written late in Shukla’s life, and is part of his rich body of writing about aging, and the vanity of older men.

--DR

At This Age

Some days ago, I had written an essay in great haste, willy-nilly, in the manner one writes satirical essays these days (or, truth be told, really any genre of essay) for newspapers and journals. The essay was for a humor and satire column in a fortnightly journal. Despite its lightheartedness, I’d waxed serious as I wrote. (As Firaq has said, “We grow serious once we’ve had our booze”). That is, the ‘willy’ disappeared from the essay and only the ‘nilly’ remained.

A very important philosopher in the city, who was also a great poet and storywriter, had given me the inspiration for the ‘nilly’ part of the essay. Actually, it wasn’t he who had given me the inspiration; his death had. He’d been wounded in a street accident. After being shuttled back and forth between the hospital and home for a week, he finally died. His son had known he was a learned man of the highest order, but didn’t know the names of any of his fans or friends. So the son left his newspaper office—which was just as unknown as the deceased philosopher had been to the paper—and simply imparted the news of his father’s passing to a handful of relatives. Those eight or nine people were the only mourners present to perform the last rites. Later, the news of his death eventually did spread and then there was much writing in the paper about society’s neglect of scholars—although there was still not much written about his actual death or the tragic reasons for it.

The circumstances were indeed tragic, there was no doubt about that; but what does that have to do with a writer like me, who is known for his realism and anti-sentimentality? However, it had seemed like a very fitting topic to me for writing about willy-nilly, that is, for knocking out a bit of satire. So one day, I sat down in my study on the roof, and wrote out a bit commentary until four in the afternoon.

My essay was addressed to those who would die in the future. It could be summarized thus:

“There is never a shortage of people in the funeral processions of important politicians, business men, captains of industry and officers.

“In such cases, countless institutions and establishments make sure to gather a large crowd behind the deceased, or the institutions themselves become the crowd. But ordinary people—in which category I include writers, artists, dancers, pimps, clowns, etc.—can’t afford this convenience. Only a handful of people show up for their funeral processions. Therefore, if you want your funeral to come off with great panache, you should start working to establish a special kind of contact with your public quite a while before your death. Otherwise, not only will the newspapers, TV, radio, etc., not notice you, but even your neighbors will not notice you—or rather, your death—and later they’ll be overheard saying, ‘How very sad! But what can I say—I had no idea!’

“One should remember that for a really large funeral procession an old and tired connection with your public won’t do the trick; people forget, or they die and leave behind an indifferent generation. If you can start up a campaign of public outreach approximately two years before dying, you will find it to be the most beneficial.”

I’d also suggested some formulas for public outreach: “Start taking part in other people’s funeral processions as much as possible; join some spiritual, religious, or sectarian group; force your way onto the board of an educational institution (so that numerous teachers and students will be available at just the right time); get yourself involved in a few betterment programs organized by your caste of that type that are happening all the time for every caste”—etc. etc.

In summary, in order to gather a crowd when you’re dead, you must keep in touch with a crowd while you’re still living.

After writing this, as should be done by any important writer, I began to stroll about on the roof, feeling a bit dissatisfied with myself, but at the same time rather pleased. In the end, I went and stood against the wall and watched the chaos of the busy street below. Just then I heard the thudding of some car driving over a pothole, and then the screeching of breaks. At the same time, a kind of shadow floated through the pale sunlight, then disappeared. My servant had been standing at the gate. He called out loudly and ran toward the street. There’d been an accident.

An old man had been hit by a speeding tempo. The three-wheeler with seven passengers had sideswiped him and knocked him over and he’d gone flying from the paved road through the air, landing by the enclosing wall of my property. One immediately witnessed all the customary sights and sounds that occur after a street accident. A crowd gathered about the old man. The tempo driver, who had stopped for two or three seconds, zipped back into traffic.

“What happened? What happened?” I cried out from the roof, but I couldn’t get myself to run downstairs. For one thing, running about is not an especially seemly thing for a person of noble character to do, and for another—and this is actually the truth—I’m terrified of accidents; I just can’t bear to look at a wounded man. As soon as I see blood, I start to feel dizzy; those who can easily tolerate such sights are uncivilized in a way. Such tendencies run counter to the high culture which centuries of civilizations have cultivated in the likes of me. But just then, a strange incident occurred which forced me to rush downstairs after all.

I saw that some people had lifted the old man up very gingerly, and just when I was expecting them to lay him in some vehicle and take him to the hospital, they brought him over and laid him back down, ever so softly, directly in front of my gate. When we saw this, my servant, down below, and I, on the roof, raised our voices in protest, and I quickly rushed downstairs. By then the people who had left him by the gate had disappeared. All that remained of the crowd were ten or eleven boys, and a few women and old men. Everyone began to express their sympathy to me; one person murmured to himself, “What a terrible thing!” You certainly don’t have to travel far to hear this popular and meaningless phrase.

The old man wasn’t moving at all; who knew if he was unconscious or dead. But as horrifying as the sight was, it became less horrifying to me when I saw there were no wounds on his body and no blood anywhere. Yes, the front of his trousers was wet, but I’m afraid of blood, not water.

“You people stay right here, I’m going to go call the police; I’ll be right back,” I said, and briskly walked off to my comfortingly familiar sitting room. I felt much reassured there, and the familiar surroundings made me feel clear-headed when calling the police.

Who says you can’t count on the police? I called the station, and within five minutes, the mobile unit appeared at my door. Of course, I did stay in the house until they came and the servant had informed me of their arrival—what could I have accomplished by going outside, anyway?

When the police came, I was overjoyed on two fronts: first of all, my responsibility to the old man had now come to an end; and second of all, my credibility had grown in the eyes of the onlookers and neighbors still waiting in the street. They had seen how a whole police unit—an assistant inspector, a head constable, and three officers—appear at my door moments after I dialed the phone. The old man still lay before the gate, not moving in the slightest. When I saw the effect of the police presence, I no longer harbored any bitterness towards those who had left the man there. I felt concern for the old man, of course, but this concern was perhaps the result of my sense that I would have to play an important role in this whole mess. Just then, I urged the head constable, “Please don’t waste time making inquiries right now. You can make inquiries later; do take him to the hospital first, please. Who knows, maybe he’ll survive.”

Actually, the police had already started making inquiries immediately on arrival—it was only afterwards that they’d paid any attention to the old man: Does anyone know who this is? What’s his name? How did the accident occur? Were any of you on the scene? What was the tempo’s number? Then what were you bastards doing here? How did the tempo come up to the gate and hit him? It hit him over there? Right there? Then how did the body get over to the gate? Who were the assholes who pulled him over to the gate?

The curses of the police officers grew sharper during the questioning in direct proportion to the successive revelations of the ridiculousness of the accident. What was surprising was that whatever I said seemed to calm them down. For some reason, they spoke to me not as police, but as civilized men. Afterwards, I thought of a reason for this. It might have been because I was attired in a freshly laundered homespun kurta-pajama. I thus earned the right to respect in their eyes by virtue of my unfamiliarity: perhaps they assumed I was some unknown hero? Or a great villain?

“Don’t worry, he’ll live,” said the Assistant Inspector, opening his mouth for the first time.

Water had already been sprinkled on the old man’s face, but nothing had come of that. Urged on by the Assistant Inspector, the Head Constable then walked over to the old man’s motionless body. He dug the toe of his boot into his ribs.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

There was no reply. Then, abandoning the foot method, he resorted to using his hands and felt the old man’s pulse.

“He’s not dead,” he said. He turned to the officers. “Take him away…to Ramnagar Hospital.”

The officers busily selected two rickshaw drivers standing in the crowd and told them, “Pick him up and put him in the jeep…not on the seat…down below…oh, come on now, down below, that’s right, on the floor…”

As though these men had left behind their sharecropping fields, their harvest, their Neem trees, and come to the city solely for this purpose.

There was still some reason for optimism. The Head Constable shook the old man, who was lying on the floor, and said, “Sit up!” But this had no impact. Then he sat the old man up, bracing his neck, and told him, “Sit up, stay sitting up!” This time there was some movement in his eyelids, and a faint moan emerged from his mouth. But he couldn’t follow the Head Constable’s orders and collapsed on the floor, his body limp.

“Please don’t take him to Ramnagar Hospital. There’s no counting on the emergency services there. Take him to the Medical College. There…”

The Assistant Inspector must have started losing his patience; he interrupted me in the middle of what I was saying, and said, “You’ve done your duty, now let us do ours.”

The next day, before sunrise, contemplating infirmity and old age, I awoke, performed my water inhalations, drank tea, relieved myself, brushed my teeth, did my breathing, yoga and exercises, read the newspaper, and had breakfast. After all these activities, my real work began: the creation of immortal prose, that is, literary activity.

But something was bothering me; I felt as though I should be doing something else today. Was I longing to go to the hospital and find out how the old man was doing? Possibly. But was it really necessary for me to go to the hospital? Yes and no. If he was alive and needed anything, I could do something about that without putting unnecessary strain on my resources and capacities. But there were also several arguments in the ‘no’ column. There’d been an accident. It was over. Why should I stay involved? And wouldn’t it be a bit dramatic to get myself mixed up with the hostile environment of a hospital by asking after the welfare of a stranger for no reason?

But “dramatic” was what decided it. Generally, I’m against drama. But should I stay away from it just so no one will consider any of my actions dramatic or present them as dramatic in the papers? Should I fear being accused of being dramatic—especially when I was going to do something inspired by a pure human feeling?”

I knew that the police wouldn’t take the old man to the medical college, so I went to Ramnagar Hospital. Once there, I was unable to learn anything about the patient for some time. How can you find out about someone if you don’t know their name? And then, all the doctors had been on strike the day before. (At another hospital, a patient had slapped a doctor. Nobody had helped him. No one had come forward to beat the patient in retaliation. The administration remained neutral, as part of the philosophy, ‘The law has been broken, and will take its own course.’ This was a purely symbolic one-day strike against the administration’s stance.) On that day, there was no longer a doctor’s strike; nonetheless, Ramnagar Hospital was still nursing a strike hangover, so most of the doctors had not reported for duty.

I kept asking people the same question: An old man was brought in for an emergency—there was an accident. The police brought him in. How is he now? Where is he? In some ward? In the morgue?

After much running about and many questions, a nurse finally told me, “He’s not in a ward, and he’s not in the morgue. They brought him into the emergency room yesterday,” she explained. “I told them all the doctors were on strike; the patient couldn’t be admitted. The policemen said, ‘Okay.’ After that they put the patient on the stretcher themselves, brought him inside, and stuck him on a bed in the emergency ward. The inspector said to me, ‘Sorry, Sister, we can’t do anything about it; you do what you have to. A car hit him and threw him to the side of the road. We don’t know how wounded he is, but we’ve confirmed he’s still breathing.’ Before I could say anything, they’d started up their car and driven off. I wasn’t even able to ask them the name or address of the patient.”

I explained to the nurse that she wouldn’t have learned anything even if she’d asked.

“I examined the patient as best I could. It didn’t seem like he was especially wounded; just in shock. But making such an assessment without a doctor is dangerous business. He could have had some kind of brain injury, or he could have been bleeding internally! Of course, even if a doctor were here, it would be difficult to tell that. We have no neurologist here; no neurosurgeon; we don’t even have a CAT scan machine….

“Slowly, he began to moan, and right around midnight he became fully conscious. He asked for tea; I was drinking some myself. It would have been hard to get another cup of tea from anywhere. I gave him a few sips of my own. He drank it, said, ‘Thank you,’ and then went to sleep.

“After that, I fell asleep myself. Very early in the morning, I woke up and saw his bed was empty. He’d left.”

Said the nurse, wide-eyed, “What he did was quite dangerous.”

There are two or three established camps of writers and critics in our literary tradition when it comes to the question of evaluating excellence. Their assumptions and views are well defined and their philosophical significance lies in their belief that they differ from one another; but the members of the two camps are exactly alike in one respect. On the one hand, they consider anti-sentimentalism a righteous value in and of itself, and on the other, when alone, they all show unparalleled skill at sentimentality—or, if not all of them, then most. I count myself among the most.

And so, despite my best efforts, I wasn’t able to get that old man out of my mind. His unconscious body, ravaged by age, lying on its side next to my gate; that pair of worn rubber sandals lying at a distance; the filthy, wet front of his trousers—everything about the scene, despite its pathos, lingered in my imagination like some terrifying wraith. I also worried he might have dragged himself out of the hospital and now lay in a bush by the side of the road, having breathed his last, or in the process of breathing his last.

I felt terribly agitated for two whole days. On the third day, my sentimentality began to abate; by the fourth day, it had abated completely, and the usual components of my daily life, that is, food, sleep and fear, returned to their natural rhythms. On the fifth day, I was standing at my gate watching the spontaneous ebb and flow of passengers and pedestrians, when I spotted the same old man staggering along down the street. He walked right by me.

He could have been drunk, but for some reason, I was sure he wasn’t. He was in poor shape, however. Nonetheless, I took a sigh of relief. He was alive.

But was he truly alive? He walked down the street, not like a man, but like the shadow of a man; it seemed as though with each step, he expanded, then contracted. He staggered along. Even when moving forward sometimes it seemed that he wasn’t making any progress, just spinning in circles. Was that really the case, or did my sight deceive me?

It had rained, and there was an excess of mud and water on the sidewalks and on the street since there were no gutters along the side of the street, so when it rained, it was the street that did the work of gutters—and in any event, it was already all broken up and full of potholes. I kept watching the old man; I knew he was walking; but it didn’t seem as though he had any destination. His entire body had become a locus of pointless movement. I wanted to say something to him, but by then he’d already walked on and I couldn’t even imagine what I would say if I’d wanted to.

He just stumbled along in the haze of the cloudless evening, unaware of the anarchic traffic that surrounded him. There were a huge number of vehicles of all kinds ahead of him and behind him, to the left of him and to the right of him: cycles, rickshaws, scooters, cars; it was quite noisy, and everything seemed to be moving at an impossible speed. I wondered: is he really unaware of them; or is he daring them to attack him? Could it be that he was challenging them; that he was saying “Hear ye, all the city’s vehicles, all the tempos, motorcycles, scooters, Marutis, Peugot-Cielo-Zen-Indica-Ford-Mercedes! Come, I stand before you unarmed, crush me! Free me from the cruel cycle of life!”

After imagining all this, I began to analyze myself: What is it about this man that’s begun to seem so incongruous to me? Without knowing anything about him at all, I was dragging him toward self-destruction in my mind; I was thinking up incisive terms like “life’s cruel cycle” for him!

The next time I saw him on the street, I was more alert than before. Right as he walked by, I cried out, “Hey!”

That day the street was sunny, the autumnal foliage sparkled, the weather was growing cooler. He was walking along as before, with the slight difference that this time he was dragging his feet rather than stumbling.

I called out to him again, “Hey, I’m talking to you, sir! Can you come over here a minute?”

A scooter drove by, nearly hitting him. Unaware, he stood where he was. Slowly he turned his entire body—this task could have been accomplished by simply turning the head—and peered at me through narrowed eyes. I don’t think I’d ever seen such a lusterless face, such dull eyes before. I felt as though he couldn’t see me, so I called out: “Over here…come over here, toward the gate!”

Slowly, as though guiding himself with the sound of my voice—he came toward me; continuing to peer at me through narrowed eyes.

“You didn’t get too hurt that day, did you?” I asked

He thought a bit, then asked, “Which day?”

“That day the tempo knocked you over near this gate.”

He stood still, his head down; then said after much thought, “The nurse was very nice. She gave me some tea.”

In other words, he didn’t remember the accident, his unconsciousness, the police, the emergency ward—none of it! All he remembered was the nurse! Is this what they call “a lust for life?”

I thought of a joke. “What did she look like?” I asked. “Dark or fair?”

“I don’t know,” he replied in a despairing tone. “I couldn’t see. I lost my glasses. I lost them that day.”

“Can you see me right now?”

“You look like a blot. I lost my glasses,” he added.

I didn’t fancy being compared to a blot, but, under the circumstances, I let it drop.

“Aren’t you afraid of walking around in the street without your glasses on?”

He shook his head slowly from side to side and said, “What do I have to fear at this age?”

“Death,” I could have replied; but I didn’t. That is the sort of fear of which I myself am terrified.

All of a sudden, I decided that I could help this poor man: I would take him to his home in my car. I had made my decision, but I laughed at myself as well. I was reminded of my humorous essay, “Some Pointers for Getting a Crowd Together for Your Funeral Procession.” I felt as though I was recruiting someone for my own funeral procession, though he didn’t seem quite up to it in terms of age. I laughed at myself and then felt ambivalent.

“Where do you live?” I asked.

In response, he gave the name of a fashionable neighborhood that was about one and a half kilometers from my home. I asked, “Is the house yours?”

Automatically, the formal ‘you’ had popped out of my mouth in place of the informal term I had been using. He thought for a bit, then said, “It was; now it belongs to my son.”

“You shouldn’t walk down the street without your glasses,” I said. “Wait, I’ll take you home.”

“No use,” he muttered.

“Please wait,” I insisted.

After I brought the car out I asked the servant, “Do you recognize him? This is the same old man—the one in the accident that day! He’s lost his glasses.”

“I put the glasses in my room,” said my servant. “After the police left, I found them lying near the wall. I'll go get them.”

He went and got the glasses from his room; actually they were just the frames. The lenses were missing. The servant explained that the lenses must have broken and fallen somewhere around there.

The old man kept objecting, but somehow we got him to sit in the back seat of the car. When the servant handed him the glasses frames, he shook his head and muttered, “No use.”

The frames were worn but they weren’t a cheap brand.

“Keep them,” I told him. “You can put new lenses in them.”

All the same, he continued to shake his head, and he was still shaking his head when the servant stuffed the frames into his pocket.

We were silent the whole way there. One possible reason for this was that we were sitting apart—him in back, me in front. After a few minutes, I let him out in front of his house.

It was a nice, tidy house, straight out of an ad for a paint company. There was a narrow street in front, and a park across the way. I helped him out of the car, although I didn’t like to touch him. The old man stood at the gate for a while; then, squinting, he turned and set out for the park. There was that same uncertainty and lack of direction in his gait.

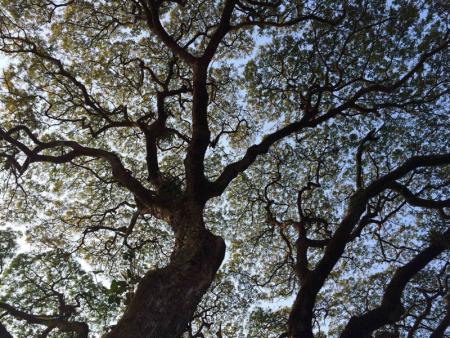

There was a large mango tree at the edge of the park across the street. Three-quarters of the trunk was ringed by a platform and the fourth section was girded by the railing that surrounded the park. There was a filthy armchair on the platform, as well as a straight-backed iron chair of the old style.

As he turned away, I stopped him. “Here is your house,” I said.

He nodded his head in agreement.

“Then why not go inside?”

He shook his head and motioned toward the gate with his shoulder.

“Don’t you see?” he asked.

On a sign on the gate was written “BEWARE OF THE DOG!” in both English and Hindi.

“But you live here; so doesn’t the dog recognize you?” I asked with astonishment.

“No,” he replied, then he stopped. “But I recognize him very well.”

“Still—your son is here, your daughter-in-law, right?” I asked weakly.

“But the dog is the one near the gate, not them.”

I looked at his worn face and for the first time, felt I wasn’t talking to an uneducated person. His mind was still quite keen when it came to irony.

I didn’t have to stick around, but I did anyway. The old man slumped down on the easy chair in the shade of the tree, and I sat on the metal chair. There was an uncomfortable silence between us.

Slowly taking the glasses frames from his pocket, he held them out to me and said, “These are of no use to me.”

“But you’ll have to get new glasses made.”

He shook his head, “No, at this age…it’s true what they say; what’s the point of throwing money down the drain? The kids will need it…I have two grandsons too.”

I should have said something, but I couldn’t think of anything to say. It seemed like he wasn’t finished talking; he was only just starting to open up.

“It’s not just the glasses,” he continued haltingly. “I’m falling apart on the inside too; I have a hernia! Prostate too…maybe it’s enlarged—who knows. I didn’t get an operation…it’s just trouble…at this age…I thought…people who throw away thousands of rupees on such things…that money will come in handy for the children, don’t you think?”

“Absolutely not, that’s not right,” I replied, shocked.

He was untouched by my reaction. After a bit, he asked me, “What do you do?”

“I write.”

Perhaps it took him a few moments to digest this. After about a full minute, he said, “I also used to write. I wrote for thirty-five years. I wrote on hundreds and thousands of files…I was in the office of the AG.”

I wanted to give some clarification, some more information; but I was silent. Then, just to say something, I remarked, “Then you must get a pension. Surely you put aside a portion of that to look after yourself?”

He muttered, “At this age…what’s the use…but for the children…”

This was all becoming unbearable for me, so I said, “Why do you keep saying ‘at this age’ ‘at this age’? At this age, there’s a lot you could consider doing! You could make yourself useful to yourself or to society!”

“Have you done that yourself?”

“What?” I gazed at his dull expression wide-eyed.

“Have you made yourself useful?” he repeated hesitantly.

He was still squinting. But I felt chagrined. I looked up. Sunlight filtered through the dense foliage onto the platform. The bright sky peered through in tiny slivers. Black spots began to swim before my eyes as I stared up. Distorted reflections of the old man seemed to expand and contract in the shadows of the leaves. In each shadow, he appeared loudly reading out a charge sheet against me from on high. And as I looked, black spots swam before my eyes; fractured offspring of the spectral images in the shadows overhead. The dappled play of light and shadow surrounded me on all sides.

I shut my eyes hard and opened them again. Shut. Open. I shook my head to bring it back to reality, but my thoughts returned to where an old man sat slumped over, wasting away, before me. Then I remembered—he had also seen me as a blot.

I felt a bit terrified, but I brought my voice under control and replied, “I don’t understand what you mean.”

“There’s…nothing…to understand…about it…it was about doing something useful…you said that to me, so I asked you the same thing.”

He fell silent.

All was still. Not even the tweeting of a bird. There was silence all around, within me and without.

He said, “Whatever happens to me happens. But you’re still middle-aged. You have plenty of time…”

Or very little, I thought.

He suddenly stopped talking. The worrisome thing was that there wasn’t even a hint of accusation in his voice, it was like a deep sob.

He still held the glasses frames in his hand. I slipped them back in his pocket, got up quietly and went away.

I drove home rather quickly—as though I hoped to make some special use of the moments saved in this manner. It was odd. For a while, I felt keenly the need to use properly each and every valuable moment of life. And quickly too.

But I wasn’t entirely sure how to do that. That evening, I phoned my editor at the newspaper. That article of mine, ‘Some Pointers for Gathering a Crowd at Your Own Funeral Procession’ that I had found so amusing—now seemed ridiculous, downright pathetic….

How ironic that even when criticizing others, my need to present the moments of my life for some special purpose hadn’t irked me till today; on the contrary—even just as a joke—I was advising others to devote their remaining moments in this life full of possibilities to sinking into a swamp of wretchedness. To waste them preparing for their own future funeral processions.

Now there were no slivers of sky above, no blinding spots of light and shadow; there was just an open blue sky, but I felt as though I was locked up in a room. I’d been locked up there for years, for centuries even, and the roof of the room was slowly falling in.

I begged the editor to send back ‘Some Pointers for Gathering a Crowd at Your Own Funeral Procession’ immediately.

But he was overjoyed with the piece. He started talking before I even had the chance to finish speaking, “You’ve written an amazing thing, Bhai Sahib! Your essay has gone to the printers, it’s probably already been printed. Vah! Only you could write something like that…”

He completely ignored my attempts to stop him, and continued to speak, using all the modish words of praise that are current in criticism these days, “…the sensitivity you’ve shown in holding a mirror of social reality up to a phenomenon as horrifying as death in your humorous style, and the concern you’ve boldly shown toward so many of life’s problems! Please, another essay just like this in two weeks…”

I had put down the phone, but his voice continued to echo in my ears, amplified a hundred times over.

--Translated from the Hindi by Daisy Rockwell

Daisy Rockwell is a writer, painter, and translator living in Vermont. She holds a PhD in Hindi literature from the University of Chicago; her translations of Upendranath Ashk’s novel Falling Walls (2015) and short story collection Hats and Doctors (2013) were published by Penguin Classics, India. She has published many story translations, a novel (Taste; 2014) and The Little Book of Terror (2012), a collection of paintings and essays on America’s War on Terror.