Gentian Çoçoli

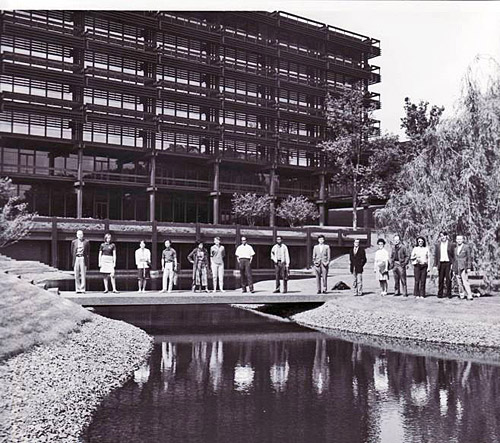

In the years since the fall of communism, the poet Gentian Çoçoli has occupied himself with the task of introducing Albanian readers to important British and American poets of the twentieth century previously unavailable under the old regime. He fills in these literary gaps with his translations of T.S. Eliot, Robert Lowell, Elisabeth Bishop, Seamus Heaney, and Jorie Graham, among others. His prolific work as a translator from English, with all of its personal and political resonances, was what initially compelled me to sit down with the poet and his poetry in the fall of 2006, during his residency at the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa, and try to return the favor.

But to access Gentian Çoçoli’s poety I needed a mediator: having no Albanian myself, I first engaged with the work in translation. Gentian’s wife, a Calvino scholar and professor of Italian, had translated a selection of his poetry into Italian, and I am greatly indebted to her for these translations, as they are the basis for my own. The intersection between the Albanian and Italian languages continues to be a space fraught with political tension and mistrust. The process of working with Gentian’s Italian texts therefore compelled us towards discussions of linguistic and political history, and an examination of how these factors affected the Albanian text in its transition to Italian. Together we worked to disentangle my English translations from their Italian roots and bring them closer to Gentian’s original Albanian text. This linguistic triangulation, from Albanian to Italian and then to English, has undoubtedly left a few indelible marks on these poems. But this seems only fair, as it was this process that made these translations possible.

—Diana Thow

A Lanicera Caprifoliumfor Violen |

Kete Lanicera Caprifoliumper Violen |

|---|---|

|

Backs of bird. Slopes of stem. Solutions of cloud. The flat of your hand has become threshold to the dark rooms |

Shpina zogu. Anime kercelli. Tretesire me re. Trina jote e dores prag i eshte dhomave te erreta |

A Bird in the Leg*to Violen |

Zogu i KembesPer Violen |

I. |

|

|

Or, made familiar, the calf. When I went sneaking the bed sheets in from the frost— the bird in my left leg trembled, contracted, as if, still attached to the stalk of the tibia, is it uprooting this human tree? |

Ose njohur ndryshe pulpa. Kur dola tek ia hiqnim eafit mu nen hunde eareafet – zogu i mengjer i kembes u drodh, u tkurr, a thua puq si qe me fyellin e kercirit Mos po shkulet rrenje kjo peme njerezore? |

II. |

|

|

How did Odysseus find himself, three thousand Novembers past |

Si u ndodh Odiseu plot tremije nentore te shkuara, |

III. |

|

|

As in another season, I entered the bedroom, |

Si ne stine tjeter hyra ne dhome te gjumit, |

IV. |

|

|

I might have known the immediate past her calves in my palms hands cupped under the front gate of my arms, like a cloth flung into the wind under a clouded twilight— |

A thua njoha te saposhkuaren pulpat e saj pellembeve te mia kupes se duarve nen Deren e Madhe, si teshe pambuku kafazit te kraheve, nje buzembremje bryme – |

—translated by Diana Thow

Diana Thow is an MFA candidate in literary translation at the University of Iowa. She has published her work in The Columbia Review, House Organ and Words Without Borders.