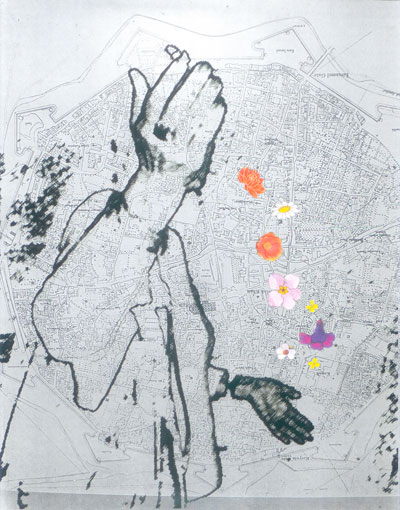

Nicossienses & Roses

Niki Marangou was born in Limassol. She has published poetry, fiction, translation, and has won literary prizes and awards. Her work in English translation includes Selections from the Divan (2001), From Famagusta to Vienna (2005)

The title comes from Chamberlayne’s Lacrymae Nicossienses, published in Paris in 1894

Nicosia, Christophoros was saying, has a tension generated by the Green Line. Those who live here long to cross over to the other side and those living in the north want to come south. This creates a passion in the city. The city bears a resemblance to Constantinople and Salonika, but none to Athens.

We were sitting on Constantin’s terrace, the city stretching out around us, the two main shopping streets, clusters of palm trees, Agia Sophia with the two great minarets was hidden by some modern buildings. It was such an important church, I said, that the Lusignan Kings were crowned here. REGES HIERUSALEM ET CYPRI. The voice of the imam could be clearly heard. It was Sunday and the streets were empty. Only some confectionaries were open and, on the pedestrian thoroughfare, some passers-by were peering into shop windows. A huge moon was rising, like a slice of watermelon.

|

| Katerina Attalides, born in Nicosia, Cyprus in 1973, studied history and painting in France and Greece; her work is exhibited regularly in Cyprus and internationally. The images in this issue are from a series called “Nicosia Untranslatable Passage.” |

I came to Nicosia when I was four, when the clinic my father was building near the General Hospital, opposite the Courts, was completed. I rode my bicycle up and down the long, endless corridor of the clinic. Even I, then only a child, felt a certain strain coming to Nicosia from Limassol. A closed society of civil servants, colonialists, and very different to the Limassol of merchants and merrymakers. I retain very few memories of those first years in Nicosia, while I can describe Limassol’s every corner. Receptions at Government House, the Queen’s Birthdays and my mother’s evening gowns replaced Limassol’s festive gatherings around the large, square dining table. At elementary school, my mind was aflame with the EOKA struggle against the British. I suffered greatly when my parents brought home an English lady to teach us the language, and I considered them traitors.

We lived near the river, in an area with tall trees, eucalyptus and palm, very close to the Turkish quarter of the city. My mother and I visited the Turkish quarter daily, to shop at the municipal market and pick up my father’s mail from his postal box at the main post office. I liked the Turkish quarter, ever since I was a child I had a love for history and old buildings, and I found all sorts of pretexts to wander there. Streets of different trades stretched out in all directions off the church of Agia Sophia. Tiny domed shops with goods hanging from nails on the wall or resting on shelves. Craftsmen sat working before small, low tables. Mattress-makers with multicoloured duvets and pillows, pink, mauve, orange – Turkish colours, my grandmother used to say whenever I wore any bright-coloured clothes. Further down were the shoemakers, with their leather boots and colourful slippers hanging, the halva sellers, with large pieces of halva stabbed with a knife, the street of the blacksmiths, the street with the fabrics.

|

| Famagusta Gate Photo: Niki Marangou |

We would enter the municipal market, my mother and I. It smelled of pastourma, cheese and flowers. She always bought the meat from Hasan, who had the best. She bought the fish from Andreas and the vegetables from whoever had the freshest. They all knew my name and would give me a bread roll or whatever else they sold in their shop. The Turks and Armenians all spoke Greek. "Good to see you!" I always went to the market with her.

I got to know Nicosia better in the 1960s when, as a teenager, I used to get around town on my bicycle. Father was very strict. I was only allowed to leave the house for lessons. Even to the British Council I went in secret. But Father never said no to lessons because he believed his daughters should be educated. Using one lesson or another as pretext, I would run away from home, often ending up at the Turkish quarter. I arranged for different lessons that would give me an opportunity to get out. I had discovered an Armenian woman on Victoria Street who taught typing and shorthand. Her mother would sit in the overhanging alcove watching the traffic on the street. The Armenian Church of the Virgin of Tyre stood across from their house. I had then bought the Gunnis book, in which I had read that the church had also been a storehouse for salt once. During the Ottoman siege of Famagusta in 1571, the Armenians, who hated the Latins, assisted the Ottomans, who, on the fall of the city, granted them the church as a reward. I would read the book and imagine that I was an archaeologist, and with great enthusiasm I would discover such and such an inscription or tombstone, as if no one had set eyes on them before me.

The road of the goldsmiths had tiny shops with rudimentary window displays. The merchandise was piled up inside English biscuit boxes, in which I rummaged for hours. I found a brooch in the shape of a hand holding a flower, a small earring of the red Ottoman gold made with a lot of copper. Everything was very cheap then and, from time to time, I could afford to buy something with my weekly pocket money. I remember pendants on silver chains used for the poll tax, which the Greeks had to pay to the Turks. Anyone who did not pay the tax had his head cut off. I would stare at these boxes, engraved with representations of executions but I never bought one. There were also silver wedding bands. During the war in the 1940s, many women exchanged their gold wedding rings for silver ones, inscribed with “War of Liberation 1940”. Most goldsmiths ;were Greeks who, after 1963, left and dispersed all over town. I met one of them, Eteoklis, years later. He had tried to reopen his shop but he could not make ends meet, readymade jewellery was being imported from abroad, and there was no demand for the handmade. So he opened a tavern, well, a sort of tavern, it was just a bench in an old house where he and his Spanish wife lived. He had become an alcoholic.

As I became interested in boys, the first rendezvous took place on the domes of Agia Sophia. We used the hollow space between the domes like a chaise long made of stone. I watched the valley turn green in the spring and yellow in the summer. I would climb up the narrow minaret stairs and the whole of Nicosia lay at my feet, all the way to the Pentadactylos range. Sevah the Seaman galloped from the one minaret and Jane Austen from the other. I read incessantly. I carried on going to the Turkish Quarter even when roadblock s were erected on both sides. As a young girl on a bike, no one thought of stopping me.

The line of division cut the town in two precisely at Hermes Street. That was the street through which we passed almost daily with my mother. Endless, long and narrow shops with glassware, plates, metal toys, a cascade of colours, the first plastics in pinks and yellows, Chinese tin plates with fish painted on them. The area is desolate now, the shops have moved elsewhere, at the SPITFIRE coffee shop by the Paphos Gate you can barely make out the sign, an old Vespa rots away in a deserted shop, sandbags, trenches.

I left Nicosia in 1965. I went to Berlin to study. There, I experienced a different Nicosia, the nostalgia for it. I returned in 1970 to find the town changed, but I had changed too. I had lost my bearings and I could no longer either write or paint. I wrote articles about the “New tendencies in European Socialism” which were well received, but I had been crafted with a north European sadness. I had lost my pencils. Only the torpid Nicosia afternoons helped me remember who I was. Idleness, and palm trees on the horizon. And the sea.

Before the invasion of 1974, Nicosia was practically a seaside town. In twenty minutes you could reach the sea. The car climbed uphill and the road would then abruptly descend towards Kyrenia, towards the sea – an enchanted sea. I often close my eyes and make that mental journey to the sea. It has been 26 years now. To reach such a sea now you have to travel for more than two and a half hours. The sea has vanished from the everyday life of the city. Looking northwards to the Pentadaktylos Mountain that hides the sea, I see a huge Turkish flag painted on the mountain. I avoid looking north.

I often walk in the old city, the half that is left. All the streets end up on sentry posts. I walk down Ledra Street, the old central shopping street that has now become pedestrian. At the far end, you can make out the minarets of Agia Sophia. During Ramadan, small multicoloured lights hang between them. I turn right to reach the church of Phaneromeni, the hammam of Emerke in the heart of the red light district. ‘Emerke’ comes from Omerye mosque, the mosque of Omar, an old monastery of the Augustinians that became a holy place for the Muslims when, legend has it, Caliph Omar spent a night there. The monastery had once been a holy place for the Latins too. Old chronicles speak of the imperishable body of Saint John de Montfort. John came to Cyprus in the summer of 1248 with Saint Louis to prepare a crusade to the Holy Land. They spent the winter in Cyprus and an epidemic decimated their army. Saint Louis lost more than 250 knights. That winter, John died and was buried at the Augustinian monastery. Stories have been told of a German pilgrim returning from the Holy Land who spent a night of prayer next to the Saint and then bit off a piece of his shoulder to take with her. Her ship, however, would not set sail until she confessed her deed and returned the holy relic, which grew again on the dead body.

|

| Photo: Niki Marangou |

Nicosia is full of such stories, as are all old cities that carry with them layered memories. Further down, the Dragoman’s mansion and the old churches. The old town has a series of beautiful old churches with exquisite icons. Often, the donor who paid for the painting of the icon is depicted at the bottom. Dutch merchants, Latin ladies in lace, fine-looking deceased maidens in scarlet gowns with their hands crossed on their chests, children wearing strange hats. The Holy Week services in those churches are devout, with canopies decorated with flowers by neigbourhood girls, following ancient customs of Adonis or Osiris. Only in those churches of the old town do I like to listen to the Easter services. Everyone is there. The man with the ancient Greek profile, the Romans, the Lusignan ladies with nets in their hair, the Saracens, the Copts, the Nestorians, Marcus Diaconus, the young woman dressed in black, the theologian in the old-fashioned suit, all dazzled among the gold and the velvet “for fear of the infidels”.

Further along, the Cross of Misirikos, which is a mosque, reveals the full confusion of this city. An old Byzantine church of the Cross, with gothic, Italian and Frankish elements, ‘Misirikos’, which perhaps comes from Misiri, Egypt in other words, and with a minaret.

People deserted their homes along the Green Line, the line that divides the town in two. Those houses then became workshops for Gabriel the tinsmith, or storerooms for Petros, the itinerant seller, to keep his carts which, in the morning and depending on the season, he fills with lemons, melons or candles for Easter. Next door, one-armed Paul cuts wood, Stephanos runs the hammam, and Mr Spyros mends shoes. On the wall, someone painted the word “Respect”. At night the streets are deserted and anyone walking on the city wall lined with palm trees may suspect a sea lapping underneath his feet, or at least a river. But Nicosia has no oasis of water to disperse the summer heat of the Mesaoria, the plain that stretches around the city, yellow for the best part of the year. It is in the summer heat that I like Nicosia most, when a west wind picks up at night and the scorched city breathes a little. And everyone goes out into the gardens and balconies.

At the beginning of the 20th century, when the city walls could no longer accommodate any new houses, the first neighbourhoods were built outside the walls, with beautiful colonial or neoclassical houses in spacious gardens. These are the most beautiful neigbourhoods of the city, which have been thankfully preserved, for those built in recent years have never managed to become true neighbourhoods. Money has come to Nicosia in the last few years. Following the Turkish invasion, many Cypriots who had lost everything went to the Middle East, worked hard and returned to rebuild the country. Wealth is visible in the new areas of the town. Houses imagined by their owners through TV serials and in which, once they inhabit them, they may feel estranged. These areas are drained of colour, the new houses with tall columns and endless rooms could be just anywhere.

It is the old town that defines me, the sense of history that each crumbling wall carries within it. It is there also that I can sense Nicosia’s geographical location facing the East. And as the years go by, I, the once passionate traveller, no longer feel the urge to leave. There are times when it seems the whole world has been confined to my garden where

In company with the aphid and the caterpillar

I have planted roses this year instead of writing

poems

the centifolia from the house in mourning at Ayios

Thomas

the sixty-petaled rose Midas brought from Phrygia

the Banksian that came from China

cuttings from the last mouchette surviving

in the old city,

but especially Rosa Gallica, brought by the

Crusaders

(otherwise known as damascene)

with its exquisite perfume.

In company with the aphid and the caterpillar

but also the spider mite, the tiger moth, the leaf

miner,

the rose chafer and the hover-fly

the praying mantis that devours them all,

we shall be sharing leaves, petals, sky,

in this incredible garden,

both they and I transitory.

Translation of the text, Xenia Andreou; of the poem, Stephanos Stephanides

Xenia Andreou was born in Nicosia in 1967. She studied history at Southampton and Oxford, and taught the subject at secondary school level. For the past decade she has been a freelance writer and translator. She lives and works in Nicosia.

Stephanos Stephanides was born in Cyprus. He left the island as a child and lived in several countries for more than thirty years before returning to Cyprus in 1992. As well as English, he is also fluent in Greek, Spanish, and Portuguese. Selections of his poetry have been published in about ten languages, and he has received prizes and awards. He is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Cyprus.

6.3 Summer 2009

Excerpta Cypriana

EDITORIAL

STORIES & MEMOIRS

POEMS

- Theoklis Kouyialis: Mosphilo Jam & The Turkish Woman Bahire

- Elli Peonidou: In Autumn They Descend & Djelal of Ayios Theodoros

- Neşe Yaşιn: The Big Word & The Light Rising Inside Me

- Giorgos Moleskis: The Water of Memory & The Paternal Home

- Jenan Selçuk: The Date Palm & Decomposition

- Lisa Suhair Majaj: Asphodel & Olive Tree

- Paul Stewart: Wanting & The Garden

VIGNETTES & POEMS