One November Night

Stavros Stavrou Karayanni’s research and creative interest is in the cultures, genders, and sexualities in the Middle East. He is the author of Dancing Fear and Desire: Race, Sexuality and Imperial Politics in Middle Eastern Dance (Wilfrid Laurier UP 2004) and is the editor of Cadences: A Journal of Literature and the Arts in Cyprus. He teaches English literature and Cultural Theory in the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at the European University Cyprus.

I open the door to find you standing outside, leaning on your bicycle, your clothes dripping with rain one November night, your face gleaming with a tender, humble, polite smile. I welcome you and you step inside, your shoes wet and your bicycle tires inscribing with fine lines of mud their geometric pattern on the flagstones. You have brought me dhal with curry that you cooked in the afternoon after work. I receive the plastic bag from you with joy and we walk towards the kitchen.

|

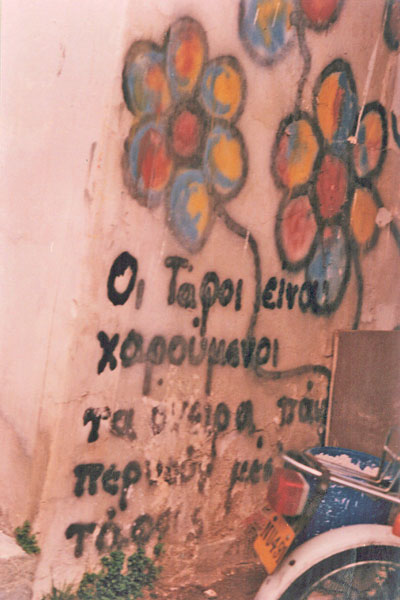

| Photo: Kathleen Cosimano Stephanides |

In the English 103-Composition course I assign an essay on the subject of migrant workers in Cyprus; ‘foreign’ workers we call them. I explain to the students that they need to think of a thesis, a direction their essay will take, and a number of arguments which they will support with relevant details and examples. The class is mostly made up of Greek Cypriots and very few international students. I write the students’ points on the whiteboard: “they take our jobs away from us and deprive us of our earned rights in our very own soil.” “But they do work that most Cypriots do not want,” I feel it necessary to interject. And even if Cypriots want jobs they will certainly not work under the conditions that migrant workers accept and certainly not with the same remuneration. “They bring drugs and violence and they commit crimes,” one female student says, her words echoing like a well-rehearsed line from a play acted out in the media and in public venues. “We have no peace of mind anymore,” another one adds as if to round off an incomplete statement. I get so dejected by these remarks that I am at a loss for a proper and effective response. “We have had violence before,” I think out loud deliberately. Our young republic was born into the violence of ΕΟΚΑ Β’; bombs exploding in Nicosia and civilian murders that remain uninvestigated and the murderers unpunished. We have graduate certificates in violence, we do not expect the poor migrants of the Philippines and Bangladesh to furnish us with such action and glory. The international students in the class are silent with the exception of one, from Nepal, who is particularly vocal and keen on expressing a firm position on the subject. “They are making Cypriots richer,” he says quite suddenly, without warning, his words crash landing on the hard and obstinate tarmac of Cypriot consciousness that paves the classroom. “They are not paid the salaries they are entitled to and often they do not get paid at all!”

I enfold you in my arms with longing and affection. I breathe in your jet black hair and your skin – soft and luxuriously dark– and I relish you in impulsive kisses. We welcome this fall into a well of desire; we sink in the sweet pleasure that we offer each other. The want that directs our bodies has a metaphysical dimension and is at the same time rooted in material circumstances. You are very young and all alone in an inhospitable place that spits at you in the same moment that it exploits you. Your efforts that remain unappreciated, your intelligence that remains unapplied, your boss that pays you a little bit of money when he feels like it and never what your work deserves—all these melt and dissolve to become the ingredients enhancing what desire you already felt for me. And I stroke your lithe body and feel it warm itself inside my hands, my fingers groping the map that helps me navigate through the paths of this love that we are sharing. Paths where my life transforms ever so fleetingly in just a handful of heartbeats and which emotion tries to count with subdued, almost mournful, elation. One moment with despair, the next moment with passion, and always with sorrow and Lorca's lament, as I hear it adapted in a Greek song, "oh, the love that flies with the wind, never to return..."

The college cafeteria is frequented almost exclusively by Greek Cypriots. If any international students appear they will confine themselves to one corner of the large room, they will not buy coffee or cheese pie, and will not sit for long either. The realm belongs to the Greek Cypriots, young men and women who dive into and rise from the depths of the misery brought on by various crises of identity and their insecurity. As I pay hurriedly for my tahini pie, my eye catches a few of the faces in moments of self-contained elation, complacence, the superiority these young people feel, who have inherited a divided island simply because some were unwilling to share it with certain groups of their compatriots. And we are, of course, very proud to live on a divided island. When we deem it necessary we state that nothing is our fault and there is nothing we can do because the great powers have made the decisions regarding our future, while at other times we swell with pride over our achievements and outstanding skills in manipulating situations so as to retain agency. This is the context in which foreign workers take their place on the scene. We would not like them to become extinct, not even those without papers (the “illegals” as they are commonly called). God forbid that they should leave, because then we would have to dig our own gardens, paint and even clean our houses by ourselves. Good Heavens! Let things remain; we are nicely comfortable individuals and the bosses—who employ them with no papers and sometimes with no pay—an insidious reminder of the horrific institution of slavery.

I hand you an orange juice, a coke, and some homemade fig preserve, and see you off. You do not want to stay the night because you are working tomorrow – every day you have to go to work – and you prefer to wake up in your familiar surroundings, the room you share with three other migrant workers, the place where your things are. It’s chilly. But I wish to linger just a little at the open door, and look as you put on your hat, balance yourself on the bicycle, and slowly glide zigzag on the road that by now has begun to dry, leaving shapes that resemble the map of another world. The plastic bag is hanging on the side of your steering wheel. I stand in the doorway with my arms crossed against my chest, and watch until your figure fades in the unlit corner just further up the street, and the unknown countries are wiped away and lost in the illuminated asphalt.

Translated from the Greek by the author

6.3 Summer 2009

Excerpta Cypriana

EDITORIAL

STORIES & MEMOIRS

POEMS

- Theoklis Kouyialis: Mosphilo Jam & The Turkish Woman Bahire

- Elli Peonidou: In Autumn They Descend & Djelal of Ayios Theodoros

- Neşe Yaşιn: The Big Word & The Light Rising Inside Me

- Giorgos Moleskis: The Water of Memory & The Paternal Home

- Jenan Selçuk: The Date Palm & Decomposition

- Lisa Suhair Majaj: Asphodel & Olive Tree

- Paul Stewart: Wanting & The Garden

VIGNETTES & POEMS