India/Walking

"The great spider Kolkata will pursue her endless migrations across you without a word of anger, an accidental kick, a curse."

Michael ZELLER (IWP '02) is the author of more than forty volumes of novels, poems, stories and essays, translated into several languages.

I.

Early morning, always, in the borderland between sleep and waking, as the first sounds touch the ear, habitual clatter of street and house penetrating behind closed eyelids where dream images struggle to accommodate sounds that do not belong and yet are familiar from years of living in this place. Reluctantly the senses, still immersed in the spiralling colours of Kolkata, admit awareness of where I am. A moment’s pause to grasp the disappointment as the day’s first half-conscious thought emerges, that the city whose pulse has become my pulse is now thousands of miles away. The torrent that pours through its streets has entered my body and taken a grip on my nerves. The mind can argue as it will, the turmoil is there. Normality has not yet returned.

I had plunged into that city with a vigour that I hardly recognize, more like the wild energy of youth than anything else. I had walked without stopping, without end. I had filled myself with walking. It was no longer I that walked; it was the insatiable somnambulant onward drive of walking itself that had swept me up into the vast, violent movement that consumes every square foot of this city.

That spot, those ten by five inches where I aim to place my foot–-where I must place it if I am to keep my balance--behind me and to the right and left the assembled forces of the city seem intent on occupying that same spot, so full is it already with the metal wall of a bus, a blaring taxi, a bicycle towing a trailer overflowing with bales of cloth, two dogs, three schoolgirls in uniform, a street vendor, a beggar on a sheet of cardboard, a white-maned, half naked old man lighting an incense stick at a tree-altar, and passers-by like myself moving in every conceivable direction. Nowhere can one escape, no quiet side-road or gateway, no entrance, not even the fork of a tree unoccupied by others, by many others. The relentless pace continues step after step, onward, onward, a pressure without friction. Not once was I hustled, not even touched. Everything around me was in motion but with a smoothness that belied the experience of any other city I knew. It was unfathomable.

Men and machines hurrying, always hurrying somewhere, but without haste. No impatience or nervousness, no sign of irritation; even the ponderous, insensate bulk of bus or truck seems equipped with sensors to prevent collision. And over this unceasing movement, which does not stop for any street crossing, the traffic lights (if they work at all) signal their reds and greens with a futility that almost evokes sympathy, while the traffic policeman, yet another dancer in the melee, waves his arms with apparent method into the void, intent only on saving his skin and his white tunic. And so this restless invertebrate of Kolkata moves its million legs by day and night, legs that are our legs, that are ourselves, and none of these millions stumbles or trips on another. Each pair reaches its appointed goal.

This miracle--I dare use the word--has only one condition: that no single item in these pulsing millions pauses for as long as a second between one step and the next. The law of motion requires each moving body to go on and on. If any stop, many others will fall over it until the whole collapses and stands still, for ever.

The only way to leave that whirling cosmos is to lie prostrate on the pavement, stretched out across it if you will, one arm under your head, and sleep. This you can do without a second thought: not the sole of a foot, not a single toe will touch you. The great spider Kolkata will pursue her endless migrations across you without a word of anger, an accidental kick, a curse. A human being, a living creature, affords no obstacle to her.

Day after day I walked the streets of this city, drawn by the sheer impetus of walking. More to see, hear and smell than the senses could assimilate. Each step a new discovery. A face, a colour, a vivid garment – a flash and it was gone. No second glance. Only the next, the next.

What drove me on? It’s hard to say. It was scarcely a matter of wanting. There was something that drew me, that propelled me without clear aim, with only a street map in my hand that I could rarely open for lack of room. Asking my way was pointless; the English spoken here and my English were two different languages. But what’s that scent of coriander, what’s cooking there? The tinkling of three small bells, is that a temple? And this street, how long can it go on, with its array of shops on both sides selling nothing but wedding cards, big gaudily coloured wedding cards, hand-made, nothing else?

And whenever I stepped aside for a moment into a bakery to collapse onto a low stool with an earthenware bowl of tea in my hand, I would already, before finishing my last sip, feel the compulsion return, the need to re-enter the flow, to be one with those others, to be a drop in that oceanic current of moving, moving, just moving. No trace of a desire any more to make notes or glance at the newspaper under my arm, glued there by my own sweat. Nothing of that remained; it was as if I had forgotten all that.

One of the very few thoughts I managed to produce in this racing of my inner motor, unceasingly fuelled by the restless walkers of Kolkata, was that if I lived in this city I would have to write differently. Here there is nowhere to withdraw, no room for the hand to wield a pen. Here, where every glance founders before it can find an appropriate word, where no second thought, no moment of reflection is possible, and I would not even want it for fear of missing the next impression and what it sets off within me, which will immediately be displaced by a third.

The thought surprised but did not disturb me. My walking body had the wrong temperature for melancholy. It glowed with a fierce heat.

No. My pencil, the staff that has accompanied me through life, I can’t use it, don’t need it here. So long as I am in this city I must go without it. Is that freedom? An unburdening at any rate.

And when the point comes for me to turn my back on the streets and return with blistered feet from hours of tramping the pavements to the calm of my room, its coolness, its massive silence, I feel neither physically nor mentally tired. The seething energy of the streets fills me even when my own is long since exhausted, a different, alien energy replete with the fulfilment that I am here at all, that I am more than my meagre self. I have soaked in it to the full.

That I can wash the grime from my skin and hair and, now that my body has calmed, feel hunger and enjoy a meal: I can forgive even that now. Kolkata is a city that knows no regret. There is no room for it on those streets.

II.

I can no longer say with certainty where I first noticed them, the walkers in India’s parks. It’s not important, because once I had seen them in that hour before dusk I saw them again and again in every park in every city of this vast land.

What shall I call them? Sports-walkers? It was the word that came to me when I first saw them, but it’s too much the product of a western way of life, too forced, too definite. No, a “sports-walker” could never display the supple ambivalence of behavior one experiences here. I must dig deeper into Indian life. Our attitudes, with their clear categories, lead one astray.

What about “Indian health-walking”? Is that any better? After all, the first time I encountered its devotees I needed an hour or more of close observation before I grasped what I was witnessing.

It was one of those late afternoons in which the energy of the Indian streets seems to rise: people were out shopping for the evening meal, the air was full of hunger, the life of the city had reached a higher pitch. Some hours earlier I had ventured out again onto the notoriously narrow pavements whose swarming currents and counter-currents bore me along virtually without aim. Just to be there in that pulsating, surging humanity, to be until the individual self no longer existed. Then to my right, hardly perceptible through the crowd, a gateway opened into what looked like a park. And in that moment I became aware of my exhaustion. The desire to withdraw from the overwhelming stream and seek rest on a bench under the trees became more urgent by the second, the impulse to flee as irresistible as thirst.

This oasis, too, was already occupied of course; but still I found enough space to sit on a bench and in a reflex action take out a book from my pocket. Opening The Wisdom of the Buddha at random I set myself to read, but no thought came. My mind sank slackly into my limbs and vanished. A nearby muezzin called the six o’clock prayer. I murmured the sentences to myself and felt an inner voice calling me to leave the activities of the day behind and prepare for evening. A protective membrane descended between my ears and the interminable clamour of traffic from the adjacent street.

After a while I was the only one on the bench. It was my bench. In front of me men and women of all ages moved back and forth: the Muslim woman in black, covered right down to the plastic sandals on her naked feet; the middle-aged man in fine twill trousers, shirt and tie, leather shoes, on his way home from the office; the elderly lady in a blue sari walking very upright, striding in fact; two young men talking together; a girl, her head veiled in a scarf, another in jeans, black hair flung open. I watched without thinking. I did not have to think. My eyes were in any case full with what I had already seen, and my sense of time grew fainter with every passing figure. I saw them coming, watched their faces as they approached and the backs of their heads as they departed, one slowly, the next more quickly. No one seemed in a hurry; here too it was motion without any ostensible aim. The scene offered little scope for reflection; I felt no absence, no lack of meaning. A good hour went by, an hour of repose. But then the lady in the blue sari returned, and the office-worker in the polished leather shoes, and the woman in black. Twice, three times they passed in front of me and disappeared from sight.

Then came the moment of illumination.

A man of about thirty--I knew him already, too. But what on earth was he doing? He walked past my bench to the point where the path turned away at right angles, wheeled on the ball of his foot precisely where a low iron railing marked the border of a flower bed and disappeared down the path. Just a moment, though--that’s not how people walk in a park. My dormant senses were immediately roused, and when after a while I saw him approaching again I was wide awake. What would he do when he came up to my bench? The same theatrical right turn? Or was that just a moment’s idiosyncrasy? No, he did it again. What was up with him? Was he odd in the head--that abrupt body-swing at the corner?

Time had me in its grip. Every second counted now as if my life were at stake. Evening or not, I was alert, caught up in a game whose rules I had to decipher. No longer the semi-comatose occupant of a park bench somewhere in India, I was part of the action again, waiting feverishly for the man who walked in right angles, waiting with the impatience of the westerner whose life is mortgaged to time. And again he did me the favour: here he comes in his shorts and cotton shirt--and yes, he’s wearing trainers. He’s my genuine sports-walker, the Indian version of those people one sees in every German city counting their laps in obeisance to the epidemic god of health.

No doubt about it, he’s one of them. But the others walking in the park, women and men, young and old, in everyday dress, sari or Muslim jilbab, with veiled head and plastic flip-flops--they’re all part of it, too. Once my eyes had been opened by the man in shorts, I understood. They were walking for health, one and all, recharging their bodies in the evening hour with the movement denied them by the working day, whether in city office or shop or behind the wheel of the ubiquitous car.

The following evening I returned to my bench in the park to check my findings, though there was scarcely any doubt by now. Many of those I had seen the day before were there, doing their rounds again, and many newcomers, schoolgirls and stout older women, as well as men of every age-–all India was on the move, obeying the voice of wellness.

And with what unobtrusive zeal, what discretion! Hardly distinguishable from the leisurely strollers who also frequented the park, mobile phone clamped to the ear (though they were in the minority), or the pair of young lovers who would rather have been doing other things. No one ran with the tunnel vision of the European jogger; no one appeared strained, let alone exhausted. The therapeutic value of movement seemed subordinate, but to what? They came and went with the natural rhythm of one who eats and drinks and talks, but to no other purpose, it seemed, than to accommodate that modicum of health whose measure is life.

Walking – India walking. After that lesson in the city park I saw it again and again, wherever I went on the subcontinent: the people of India walking themselves fit.

III.

Nimtala, Kolkata’s ancient burning place for its dead, on the bank of the Ganges. Abandoned stone-tiled squares on which funeral pyres were once stacked; next to them, empty and desolate, the stone niches in which the bereaved sat and watched the fire. Gone, all of it. Time moves faster now. The funeral pyres took too long.

Down at the river a group of young men, six or eight of them. One of them takes off his outer clothes and enters the water in his underpants, submerges himself fully and then, rising, cups his right hand and allows the water to flow over the outstretched fingers. A graceful gesture, as if he were washing them finger by finger. He climbs back up the ghat and goes towards a figure holding a dazzling white cloth over his arm, the folds stiff, unused. With the strangely calm, seemingly aimless movements one sees so often here, the bather is clad in this garment. I cannot read these gestures, they have a rhythm of their own, a beauty too great to mean nothing but themselves. Everyday gestures that yet convey solemnity, a sense of cult. Something very old is happening, and yet it is only a bather being dressed.

Nearby stands the crematorium in current use. A dark hall full of people. Several large ovens replace the funeral pyres of earlier times. They too are old: rusty iron products of an industrial age, thick with dust. Opposite them the dead are arrayed on light bamboo biers, their bodies decked in the brightly coloured garlands that everywhere in India provide a resting point for the eyes.

Their heads are uncovered.

Around the biers the families of the deceased stand, squat and sit. No one weeps or sobs. Powerful voices call to each other, giving orders. This is a place of work, not silence.

In the front row the body of an old man. Someone anoints his fallen cheeks and yellowing forearms, his hands and his feet, with oil. A step further away a strongly built woman of sixty rests her right hand on her husband’s shroud – he too had been a large man – squats down next to him, completely absorbed, a familiarity death itself cannot break. At the next bier they are busy telephoning, no thought of lowering their voices. Children run between the corpses, playing their games of catch, here as everywhere else.

Movement enters the crowded hall; next to one of the ovens it grows louder. The body on the bier is clearly recognizable now with its head of thick black hair and beard. Evidently the youngest here. How old? Forty rather than fifty. A young boy dressed in white comes forward, the bather from the ghats, holding a long, thin wand in his hand, the end of which is now ceremonially lit. He takes the flame to the face of the deceased, his brother perhaps or father, the similarity in their features unmistakeable. With burning staff he circles the bier followed by the keening family. At the head he dips the flame again to touch the bearded lips. For the Greeks the soul left the body through the mouth: ‘A kiss / Drew the last life from his lips / A genius sank his torch’ – how beautiful Schiller’s lines, that latter-day Greek. Why not in India then? After all, the death notices in the newspapers often say ‘He breathed his last.’

Several more times the white figure moves around the bier, runnng now. Helped by the others he pushes it onto a metal carriage. Cries ring out: the moment of farewell, final parting from a body that is all that remains, before it too is reduced to an image in the memory. The oven door opens, belching hot breath from the furnace into whose red gorge the corpse now disappears, to become ashes.

Next to me a man speaks, wants to explain something. There is a bone in the belly that does not burn. What the organ is called he cannot say. It is gleaned from the ashes afterwards, placed in an earthenware vessel and given up to the river. I am distracted.

Only when I hear loud individual sobs close by do I turn away from the man. It’s the boy in the gleaming white cloth, weeping now till his shoulders shake. The other members of the family stand round him, perplexed at such open grief, and slowly the cortège moves towards the door, where there is air and light. Is he weeping only for himself or as chief mourner for all? Again this multiplicity of meanings. And at the same time it’s quite simple: someone has departed. Mourning.

I follow the family out into the open. A sannyasi dances up to me wrapped in a dirt-encrusted cloth, thick red paint on his lips, his head a mass of tangled hair. Dervish-like he prances round me with long thin brown legs singing ‘Money, money, money’ over and over again. Just that one word. Money.

A beggar? A holy man? A madman?

It’s all so close at this moment. And all so one.

--Translated from the German by Joseph Swann

Joseph Swann translates from the German, and teaches English at Bergische Universität Wuppertal (Germany).

8.1 Spring 2015

Editorial

The postcard

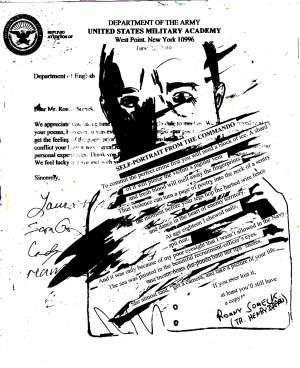

- Ronny SOMECK / Self-Portrait of the Commando

Fiction

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Blindfolded and bound in the boot of an unmarked police car, the boy was delivered to the House of Stories...

- Marie-Louise Bibish MUMBU / Me and My Hair

The Bana mboka, the kids from here, versus the Diaspora, those who banished themselves. Fresh-Bagged versus The Bottled Stuff. Rainy Season versus Winter. Stayed versus Left. On Foot versus Driving. Boubou against Low-Waisted Pants...

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Poetry

- Ariane Dreyfus translated from the French by Corinne Noirot + Elias Simpson

- R. M. Rilke in new translations by Mark S. Burrows

- Shah Hussein and Naveed Alam in a Punjabi-English dialogue. With a preface, and an interview conducted by Spring Ulmer

Non-Fiction

- Michael Zeller / India. Walking. Translated from the German by Joseph Swann

- Sadek Mohammed (Iraq), Boaz Gaon (Israel), Mujib Mehrdad (Afghanistan) on writing in a country at war

Book review