Writing in a Country at War: Three Voices

"War has become not only a theme but a technique." S.M.

These pieces were originally written (in English) in response to an open invitation to a panel at the Iowa City Book Festival in the fall of 2014. Though more than a few of the writers in that year's IWP residency were from zones of active conflict it was the three writers below—from Iraq, Israel, and Afghanistan—who stepped into the fray.

Sadek R. MOHAMMED:

Perhaps I should begin by informing the honorable audience that I am from a country and a people whose wars come in all sizes, types, shapes and colors. We have short wars and we have long wars. We have fat wars and we have slim wars. We have black wars and we have white wars. We have shaved wars and we have bearded wars. We have dirty wars and we have clean wars. We have sexy wars and we have unsexy wars. We have Latino wars and we have Asian wars. We have Iranian wars, Kuwaiti wars and American wars. We have conventional wars and we have high-tech wars. We have holy wars and we have unholy wars. We have symmetrical wars and we have asymmetrical wars. We have biological wars and we have chemical wars. We have the Saddam wars and we have the Bush wars. We have the mother of all wars and we have the father of all wars. We had the first war and will probably have the last war. We've even had a war sitting on our heads like Kim Kardashian's butt for the last eleven years. Our killers work 24/7, from Basra to Mosul and from Fallujah to Baghdad. Their latest exhibition was held on Mount Sinjar, where captive women were sold by ISIS in Mosul's local markets. For further details please see the map of a country called Iraq or simply visit a non-existent website at www.iraq.bullet. [Note: all our w's stand for war]

Writing is a very complicated process, and writing in a war zone is the most complicated of all. Various schools of criticism inform us that writing is conditioned by its circumstances and environment. If this assumption is true, it is certainly very true of writing in a war-ravaged zone. However, one must not forget that the nature of war differs from one case to another. Accordingly, the conditions of writing, by necessity, differ too. Writing in trenches, in a conventional type of war, is certainly different from writing in a high-tech modern war or, for that matter, writing in a civil, a militia or a terrorist war. Writing in the red zone, the less fortified part of Baghdad where I live and work, is one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. The enemy is always an invisible fanatic who is bent on murdering and maiming as many innocent people as possible with all manner of light weapons, and, of course, there are suicide bombers. Last year a suicide bomber killed and injured more than 90 of my students as they were reading for their final exams in a mosque near the university. Last January, as I was telling a bedtime story to my four-year-old daughter, an attack on a nearby juvenile prison turned our tiny neighborhood into a battleground between security forces and terrorists. Last winter, an unidentified person planted a bomb in my country house in the al-Nahrawan suburb of Baghdad; I only survived because I had stopped to buy cigarettes. Streets are punctuated by thousands of checkpoints made of steel, concrete and iron. The streets are also filled with the jarring sounds of sirens and the horns of military convoys. The traffic may be stopped for any reason, and you may find yourself trapped in a wasteland of meaningless existence. In this red zone, it is especially dangerous for writers such as journalists, translators, academics and poets. And of course, it is more dangerous yet if you are all these four in one, like me. In the beginning, when you realize the dangers that surround you as a writer, all you desire is anonymity and invisibility because you know that hundreds of the country's writers have been kidnapped, captured or killed. War becomes a way of life, and writing becomes a threat that might reveal your camouflage. However, slowly but surely, war wittingly or unwittingly infiltrates all aspects of writing and turns it into a war tactic. Thus, a writer may speak of:

1. Reconnoitering the world of experience.

2. Ambushing imagination.

3. Tactical forming of resources.

4. Phasing the text and/or the writing process.

5. Coding or encrypting the message.

6. Jamming readers' radars

7. Leapfrogging readers to obtain a favorable creative position.

8. Capturing the readership's imagination.

A text is a porous entity. The osmosis that exists between the real world and a text enables war to find a habitat in the text and refashion its fabric according to its own law. War has become not only a theme but a technique. Thus:

1. Poems become saturated with the lexicon of war. Here is but a sample of the vocabulary employed in poems by some of my colleagues: blood, shrapnel, uniforms, bombs, bullets, wounds, truce, helmets, berets, graves, shelters, trenches, etc.

2. Sudden ends, sudden beginnings, and the illogical organization of the various parts of the poem [the order of chaos].

3. Anger: the ranting, the cursing, the use of profanities.

4. The rhythm of war: the list, the observation post, reconnaissance.

5. Poetry as code.

6. The presence of the erotic in the midst of the chaotic.

7. Poetry as an SOS message.

8. Destruction of language.

9. Poetry as a message in a bottle for future generations.

10. Publication as exposure, making a poet vulnerable.

*

Boaz GAON:

In Henrik Ibsen's An Enemy of the People, the protagonist Dr. Thomas Stockmannn is elated, ecstatic almost, when it is confirmed that the waters of the local baths are indeed contaminated, and that no solution remains but to shut down the factories responsible and pay the necessary price - in resources, political gain or pride – to save the lives of the town's inhabitants. In the beginning, to Dr. Stockmann – the same Stockmann who at the end the play is on the verge of being lynched by a screaming mob – the mere possibility that his audience would much prefer to continue bathing in poisonous waters is unthinkable.

As a writer who's been writing in a country in a permanent state of war since I first learned to write, and as a playwright who took on the daunting task of adapting Ibsen's 19th century classic to the pollution-riddled Israeli desert of 2012--I don’t buy that.

There is no elation in delivering hard truths to audiences who "don’t want to hear it," nor is there innocence. Writers in Israel, and I suspect elsewhere, know when they are crossing the line. The line beyond which lie danger, screaming mobs, and potential violence.

Our duty as writers is to cross that line.

Our privilege as writers is to do so not by being patronizing – as Dr. Stockmann was, eventually comparing his town's people to dogs who needed to be put out of their misery – but by entering hearts, and inviting audiences to enter the hearts of others.

To me, that is our dual obligation as writers in a country at war: to cross lines across which dangers lay, and to touch hearts.

The first without the other is provocation. The second without the first is evasive, comforting and polluted, like the baths in Mr. Ibsen's play, which in our adaptation became drinking water. We did this to emphasize that in our town, at this time, no one was free – not even the writer – from committing daily rituals of conscious suicide. All under the pretext of "nothing can be done" and the "situation is insoluble."

Which brings us to the final question of what writing should be when days are measured in units of life and death, especially when the writer himself is “safe.”

In a country at permanent war, such as Israel, writers are seldom safe – nor should they be. They are part of their communities, "flesh within the same flesh" as we say in Hebrew, and it is my humble opinion that we should be exposed to the same dangers as our audiences. We should also be willing to pay the price of engaging with audiences who “don’t want to hear” since we, unlike other writers of the region, do not face immediate arrest, imprisonment or torture.

But there is another danger I must acknowledge – that of losing faith in the audiences' desire or ability to change for the better; which leads directly to a bigger danger, namely losing one’s will to write, since there is no meaningful audience to engage with.

"Words are meaningless," says Said to his wife Saffiyeh in another adaptation of mine, that of Ghassan Kanafani's brilliant novella The Return to Haifa.

I chose to believe the contrary.

I chose to believe that it is my duty as a writer in a time of war and occupation to not lose hope, and to always remember that there are people who stand to gain power, or money, or a polluted peace of mind if I stop crossing lines, or touching hearts.

The question of influence is not mine to judge, nor is it guaranteed that the desired change will happen in my lifetime. Or in the words of the Jewish Pirkey avot, or "Ethics of Our Fathers": "It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work - but neither are you at liberty to desist from it."

*

Mujib MEHRDAD:

Afghanistan is country of wars. It has been the center of great empires under the Kushans, Ghaznavids, Ghorids, Timurids, the Durrani dynasties and so on. The Silk Road passed through it, but so did many imperial armies in their expansion from one part of the world to another. Thus Alexander the Great founded cities and military bases in Afghanistan, staying for many years, while Genghis Khan’s presence in the 13th century resulted in widespread killings, including that of Attar of Nishabur, Rumi’s spiritual mentor. In the 19th century Russia and Britain attempted to install the Durrani rulers as their own puppets, and in the 20th Afghanistan once again became a battlefield during the Cold War. Soon the Taliban emerged from Cold War policies, leading to further violence, including the killing of another poet, Qahar Asi, by a rocket in Kabul. All this – coupled with Afghanistan’s ethnic and language diversity, which were highlighted and exacerbated by the civil war of the 1990s – paved the way for neighboring countries to interfere. War in Afghanistan has always been a proxy war, never our war.

War

Two leaders sleep in two beds

Two soldiers exhausted in two trenches

Two leaders laughing at the negotiating table

Two flags on the grave of two soldiers

--Samy Hemed

War is the result of the collapse of moral order. Yet sometimes I think that when we become violent, we return to our origins. War is part of mankind’s being, and our will to war is something conscious. Human beings are responsible for the circumstances they or others live in. It is why we all play our part in wars, just as Sartre blamed himself for the Second World War. This illustrates how will to war is the other side of the will to live, with greed as a constant motivator. Throughout history every conqueror has sought wealth for their empire in order to prove their supremacy over all others. The history of mankind is therefore the history of war. Today, mankind remains prisoner to this greed, with the only change being in the way wars are portrayed.

War and literature

Literature is produced in times of both peace and war. War dramatizes life, and these sad dramas are inevitably about mankind’s quest for basic rights. War thus gives literature a special taste and quality, for it creates special human beings: it destroys the bodies made by God and creates its own deformed or reformed bodies, giving birth to another kind of behavior.

War has permanent consequences. This is why our behavior today is linked to what happened to our ancestors during the Genghis Khan invasions: our bodies are new but our souls belong to the past.

The writers’ position

Mankind is shameful

With his epics

Even his defense is shameful

For he inevitably shoots at someone

Who has inevitably invaded

Writers take a position in war--for or against. Those in the latter position totally reject it, and bear witness to its destructive force, writing what is known as anti-war or peace literature. The inverse angle is to praise war: in this context, war relates to values such as patriotism and struggle for freedom. Here literature is instrumental for the stimulation of the masses.

Resistance poetry, too, can be against war or in praise of war, the latter changing it into a holy war through poetry or fiction. Another kind of resistance literature encourages is civil action and the struggle against censorship within an autocratic government. But there are also writers who justify government brutality in war. In Afghanistan in the 1980s, poets justified mass killings by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan in the name of preserving Marxist-Leninist revolutionary values. For them, literature was an instrument of propaganda and publicity.

The aesthetic effect of war

Two quivering grenades on your breast

How beautiful is your suicide bra

--Sharif Saidi

War creates unique poetry because writers in countries experiencing it are under unique emotional circumstances; they forget about aesthetics. They deploy poetry as a call to sacrifice, and to courage. In war, literature also finds itself in the position of recording events, a sort of journalistic function. This widens the distance between literature and creativity. For example in Afghanistan in the 1980s, a group of writers who were working to bring down the Marxist government from within came out with a genre we can call metaphor poetry--very complicated and full of symbols and signs that only a small circle of writers could understand. It was the poetry of a minority for a minority. In order to circumvent censorship and survive, they used too many symbols. The poets working for the government, those fighting the government and those exiled in Pakistan—regardless of their orientation all produced propaganda literature during that time. As well, during the Taliban years, when the regime punished people by cutting off their hands or even executing them, poets were producing work full of violence and religious rhetoric.

The poetry produced after the Taliban fell is my generation’s poetry. A generation born from the womb of war, and raised in the ruins. A generation that abandoned the weapons of the civil war and took up the pen instead. Even our romantic poems are full of images of war: we have been witness to the deaths of our family members, our childhood friends.

---

8.1 Spring 2015

Editorial

The postcard

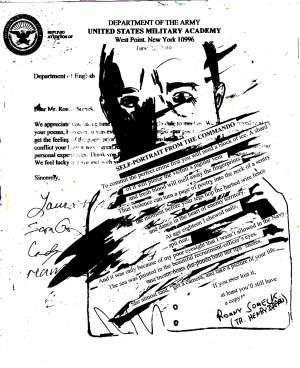

- Ronny SOMECK / Self-Portrait of the Commando

Fiction

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Blindfolded and bound in the boot of an unmarked police car, the boy was delivered to the House of Stories...

- Marie-Louise Bibish MUMBU / Me and My Hair

The Bana mboka, the kids from here, versus the Diaspora, those who banished themselves. Fresh-Bagged versus The Bottled Stuff. Rainy Season versus Winter. Stayed versus Left. On Foot versus Driving. Boubou against Low-Waisted Pants...

- Marguerite FEITLOWITZ / In the House of Stories

Poetry

- Ariane Dreyfus translated from the French by Corinne Noirot + Elias Simpson

- R. M. Rilke in new translations by Mark S. Burrows

- Shah Hussein and Naveed Alam in a Punjabi-English dialogue. With a preface, and an interview conducted by Spring Ulmer

Non-Fiction

- Michael Zeller / India. Walking. Translated from the German by Joseph Swann

- Sadek Mohammed (Iraq), Boaz Gaon (Israel), Mujib Mehrdad (Afghanistan) on writing in a country at war

Book review